CSDS POLICY BRIEF • 8/2025

By Daniel Fiott

2.4.2025

Key issues

- Despite the epoch changing nature of Russia’s war and the second Trump presidency, Europeans do not yet appear ready for more European Union (EU) defence integration;

- The European Commission has designed a credible package of defence industrial initiatives, detailed its White Paper, but some schemes risk reinforcing the very structural risks the Commission seeks to avoid;

- The forthcoming negotiations for the European Defence Industrial Programme (EDIP) will be a genuine test of whether the Union can craft a well-financed, durable and equitable EDTIB.

Introduction

Take a step back from the noise of social media and one would be forgiven for thinking that not much has actually changed in the United States’ (US) approach to European security. A lot can happen in four years, of course, but President Trump has so far not reduced American troop levels in Europe, and, despite some media soundbites, European governments are not really acting as if they take a US withdrawal from NATO that seriously. If, for example, we look at the language used after the London Summit in early March 2025, European leaders still seem to assume that the US will remain the primary security guarantor in Europe. Governments within the EU continue to act as if they have a formula for dealing with the Trump administration: play some golf, buy some planes, genuflect and, above all, do not vocally come out in support of the EU.

As no European state will want to be seen to sever ties with the US, we are currently engaged in a game of deflection based on the idea that Europeans can ride out the storm. In many respects, Prime Minister Meloni’s comments that it would be “childish” to choose between America and Europe was saying out loud in the press what many European states are thinking behind closed doors. Given the level of dependency on the US for their security, it is understandable that Europeans hold to the idea of a status quo in transatlantic affairs. Indeed, the threat of being abandoned by the US is one of the main reasons why Europeans are clamouring to increase their defence expenditures.

Yet, all is clearly not well in the transatlantic relationship. There appears to be a genuine ideological loathing of the EU in the current administration. Nothing the EU does is seen as positive in Washington today: it is seen as a trade and technology rival that curtails free speech and is a bastion of “wokeness” – and a very small minority of European leaders would agree with this. The relentless threats to seize Greenland from Denmark, and the risk that Russia and the US go over the heads of Ukraine and Europe to finalise a “peace deal”, have added to the sense of urgency in Europe. On top of this, hints that the US may weaponise Europe’s existing dependencies on American weapons systems for political ends (e.g. the F-35), has exposed Europe’s lack of autonomy.

This author has long-held that Europeans have little control over decisions in the White House, so they should instead focus on meeting the Trump administration on areas of common ground: namely, developing conventional military capabilities and rapidly ramping-up their defence industrial base. Interestingly, with the exception of Europe’s minority of neutral states, one would be hard pressed to find a European state that does not agree with this particular remedy. While most states have settled on the need to increase defence spending and build-up the European defence technological and industrial base (EDTIB), there remains no agreement on how best to organise these efforts. This CSDS Policy Brief looks at some of the challenges facing European defence cooperation today.

To agree, or to disagree, that is the question

Ever since Russia’s war on Ukraine, there has been an unprecedented unity of purpose in the EU on the need to increase defence spending and to develop the EDTIB. Looking back over the European Council conclusions since Russia’s invasion reveals a remarkable level of consistency in the overarching objectives of the Union’s efforts in defence. The 2022 Versailles Declaration of 10-11 March 2022 states that the EU should increase – preferably jointly – investments in defence capabilities, strategic enablers and innovative technologies; protect critical infrastructure; enhance military mobility; and boost the EU’s space activities. The European Council conclusions of 27 May 2024 underlined this approach while also stressing the need to militarily support Ukraine and build Europe’s air and missile defences. The 6 March 2025 conclusions went further in calling for the EU to reduce its defence dependencies while also finding new ways to invest jointly in defence capabilities, including by encouraging private investment in the defence sector.

On the face of it, therefore, EU member states have understood that they are chiefly responsible for supporting Ukraine with long-term financial assistance and military support. Most leaders are also exhibiting a desire to rapidly enhance defence spending at the national and EU levels. In a relatively short span of time, EU member states have collectively increased defence spending from €254 billion in 2022 to €326 billion in 2024. Although this is still less than NATO’s 2% target – which would have required a spend of €338 billion in 2024 – this is still a remarkable rise. And there are reasons to believe that defence spending will continue to rise in the future in Europe. Only recently has Germany announced a planned spending hike of €500 billion on defence and infrastructure, and Sweden has stated its ambition to reach a target of 3.5% of GDP on defence by 2030. What is more, the defence stocks of Europe’s largest defence companies are on an upward trajectory with the aerospace and defence sector stock index rising to a record high of 7.7% in March 2025.

Despite the impressive nature of such data, the reality is that these are largely national endeavours. In fact, for all of the fine language in summit conclusions and strategy documents developed by the EU, member states are still fundamentally at odds with one another over the direction of EU defence. Put simply, member states do not fully trust EU institutions and, perhaps more importantly, they do not trust each other. Currently, a majority of governments believe that they can develop national defence and benefit from the up-tick in defence spending without any heavy involvement by the EU. Thus, it is too simplistic to assume that any deterioration in relations with the US will automatically benefit European integration. In fact, we saw under the first Trump presidency how EU member states created initiatives such as Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO). On the face of things, PESCO represented a bold step towards EU defence integration in the face of transatlantic turbulence, but in reality PESCO was not really designed to deepen defence integration – it instead simply reinforced the intergovernmental logic of EU defence.

The truth is that any whiff of communitarianism in defence still frightens EU governments. True, EU member states did agree to create a European Defence Fund (EDF), which substantially enhanced the role of the European Commission, but we must remember that, at €8 billion spread over 7 years, the EDF was not seen as a significant threat to national interests. We have also seen several EU member states double-down on the idea of “Europeanising NATO” – or of creating a European pillar in the Alliance. While such measures are driven mainly by a fear of US abandonment, and recognising that the US through NATO provides Europe’s security, cooperation in NATO also offers those EU member states in the Alliance an intergovernmental framework that is free from seemingly powerful actors such as the Commission. Rightly or wrongly, member states believe there is a greater level of intrusion into national defence policy in the EU framework when compared to NATO.

And even when EU member states do try to organise defence cooperation in an EU setting, they prefer to develop intergovernmental initiatives. PESCO has already been mentioned, but other examples include the European Peace Facility (EPF) and the European Defence Agency (EDA). The Agency is particularly interesting in this regard because it is often seen as a foil that can be used by member states to balance against the European Commission. In fact, the EDA is the most “NATO like” body within the EU institutional architecture as it offers member states a voluntary form of cooperation that does not question the logic of national sovereignty. While the EDA does in reality hold a lot of potential to spur-on EU defence cooperation, member states have rarely used the Agency to its full potential. When member states claim they want a bigger role for the EDA, but then do not launch serious capability projects within the Agency, that is a sure sign that the body is being used as part of the internal institutional power game in the EU.

All things being equal: managing political asymmetry in European defence

The coming months will be a vital test of how European governments want to organise their defence cooperation at the EU level. For one thing, no amount of calls to create a European pillar within NATO can do away with the inherent uncertainty facing the Alliance. Yet, even so, a majority of European governments will need to step up efforts to “rescue” the Alliance in case of US retrenchment or abandonment. This naturally means a European effort to substantially enhance conventional defence, but it may even lead to more serious efforts to develop a European nuclear deterrent. Then there may also be a need to reflect on how Europeans could take control of SACEUR and other NATO offices, as well as developing the suite of strategic enablers Europeans would need to fulfil critical NATO tasks. Perhaps in this respect the real doomsday scenario for Europeans is for the US to remain inside NATO, but only to effectively kill decisions and initiatives: creating a sort of “zombie organisation”.

The paradox, of course, is that any enhanced European pillar within NATO would greatly benefit from EU support. In the context of EU-NATO cooperation, reflections on deepening cooperation have centred on how each organisation can contribute to specific policy areas (e.g. space, military mobility, maritime security). Yet, far less attention has been dedicated to seriously thinking through how any US abandonment of NATO would force together the Alliance and the EU in political and operational terms. For one thing, while NATO upholds the primacy of national sovereignty among its allies, it has never been a politically symmetrical organisation – the US has played an outsized role by providing direction, apportioning tasks and duties and quashing political differences between allies. The political dynamic in NATO without the US would be more akin to the political structure of the EU – perhaps in many ways even more complicated, given the larger membership –, and this means that some level of political symmetry between European states would be required if cooperation is to function properly. This is essential when one considers that external actors such as Russia would be seeking to capitalise on any opportunity to destabilise NATO and the EU through disunity among member states and allies.

Clearly, there could be a major role for the EU to support Europe’s defence industrial renaissance and scape-up Europe’s available military capabilities and technologies. Yet a fear of deeper EU defence integration persists. The usual characterisation of this fear is that the European Commission seeks a “power grab” over defence policy, even though EU defence initiatives do not in fact curtail national sovereign defence decisions. In reality, the EU offers a venue for member states to develop common military capabilities through financial support and a legal structure that protects EU investments from external influences and dependencies. While developing common military capabilities may not actually reduce upfront development costs, it can lead to economies of scale that are important in a strategic context of high-attrition warfare. And, what is more, the sheer regulatory size and competence of the Union means that it makes practical sense to work via the EU than through a national-only approach (e.g. military mobility).

Yet, the EU’s virtues in the defence domain can also be seen as weaknesses in the eyes of member states. Indeed, one of the other reasons why member states have been reluctant to deepen EU defence cooperation is a fear that doing so will lead to more defence market consolidation, less competition for smaller firms and states and the creation of fewer and fewer national champions that operate on an EU-wide basis. There is a fear that the objective of market de-fragmentation will lead to European consolidation around a handful of industrial players in the large member states, rather than a de-fragmentation that genuinely enhances intra-EU competition for defence contracts and technologies. The point being whispered loudly is that the Commission is somehow in cahoots with the Union’s largest defence players – such perceptions are corrosive, even if untrue. A lack of trust hampers deeper defence industrial cooperation in the EU, even though institutions such as the European Commission are ideally placed to address these concerns through reform and finances.

Fragmentation through the back door?

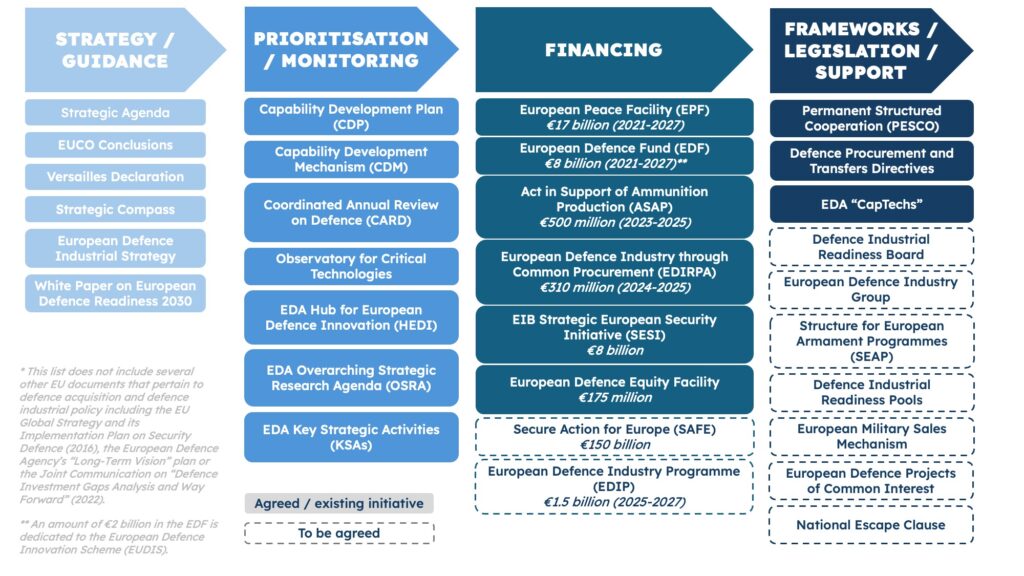

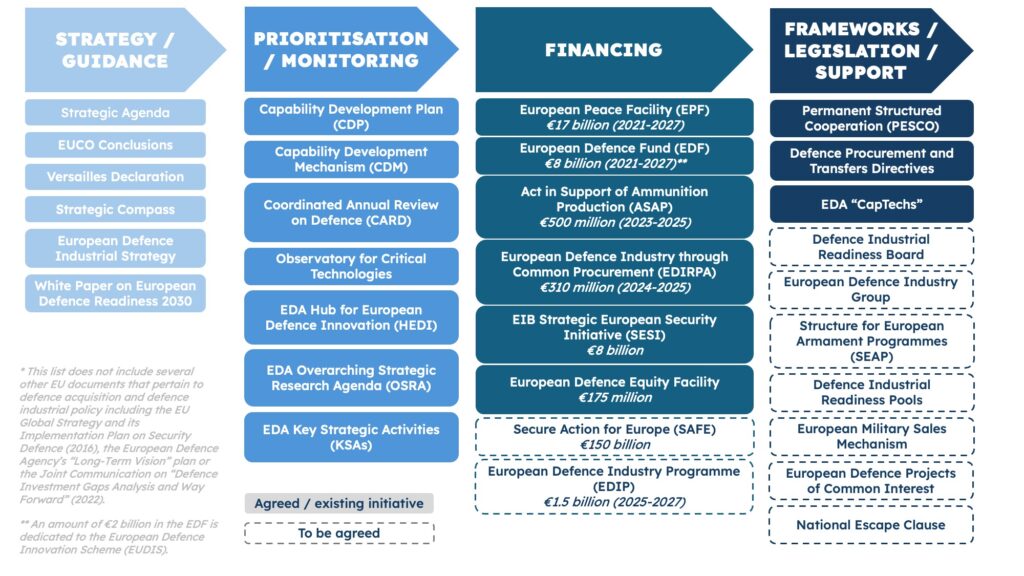

Given these political considerations, what do recent EU initiatives tell us about the future direction of EU defence industrial policy? Perhaps expectedly, the picture is mixed and somewhat confusing (see Figure 1). The White Paper on European Defence Readiness, published on 19 March 2025, outlines defence industrial measures that are geared to enhancing Europe’s response to the ongoing war in Ukraine and fundamental questions about the transatlantic relationship. The White Paper states that the EU must meet a higher level of defence readiness by 2030 by investing more in defence capabilities, technology and innovation. Aside from providing an updated threat perspective for the EU, the White Paper is built on five pillars of action: 1) a revision of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) rules to enable more national defence spending; 2) a new loan facility called the Security Action for Europe (SAFE); 3) using existing EU financial instruments for defence; 4) a greater role for the European Investment Bank (EIB); and 5) mobilising more private capital.

The second pillar of the White Paper introduces the new SAFE instrument, which would see the European Commission provide EU budget-backed loans of up to €150 billion to member states for defence. The SAFE instrument would be used for common procurement of the Union’s most urgent capability needs including air and missile defence, artillery systems, ammunition and missiles, drones and counter-drone systems, military mobility, Artificial Intelligence, Quantum, Cyber and Electronic Warfare, strategic enablers and critical infrastructure protection. Loans will be approved by the European Commission subject to member states submitting a national defence industrial plan for assessment, and a minimum of two member states would be required for a successful loan application.

Figure 1: The EU Defence Industrial Architecture

Source: Daniel Fiott, 2025

SAFE is no doubt an interesting proposal but it departs from the EU’s usual financial incentives for defence cooperation. Thus far, the Union has utilised the EDF to provide grants – rather than loans – to industries. Loans need to be repaid and it is unclear how many member states will be genuinely attracted by Commission-backed loans when they have gotten used to grants that can be utilised without repayment. Grants are also deemed more attractive for national defence account reporting, as loans show up on accounts as an expenditure. Here we should acknowledge that the proposed €150 billion loan instrument is intimately linked to national debt, and the first pillar of the White Paper related to the SGP. Future repayments of SAFE loans by member states will ultimately come from national defence expenditures, so a portion of the foreseen €650 billion in additional national spending in the White Paper will be dedicated repaying SAFE loans (if, of course, utilised by the member states).

It is also unclear whether the SAFE instrument will be able to provide favourable borrowing rates to all member states – the Eurozone 10-year bond yield sits at 3.22%, but Germany borrows at 2.68% (all rates as at 31 March 2025), which means that Berlin can borrow more cheaply than that offered by the EU under SAFE. Additionally, it is unclear today how loans under SAFE would be dispersed as they can only be accessed after the submission of a “national defence plan” to the European Commission. In practice, this may generate a reluctance to apply for SAFE loans as member states may need to submit to the Commission potentially sensitive information about national plans, and/or they may be reluctant to empower the Commission as a more central authority in EU defence. Finally, the proposed SAFE facility requires a serious reflection on the governance of EU defence tools. There is a risk of over-complication in establishing an effective and coherent relationship between the EDF, the future EDIP and now SAFE – not to mention other EU initiatives such as PESCO.

Beyond SAFE, however, perhaps the biggest concern with the White Paper is the proposed revision of the SGP rules and the activation of the National Escape Clause (NEC). Essentially, this pillar follows-up on a long-standing request by some member states to exempt defence spending from the excessive deficit procedure under the SGP. It so happens that this initiative was finally taken seriously by the Commission at the same time that Berlin agreed to amend its own national debt brake rules. The Commission is now proposing to amend the SGP rules to facilitate greater national defence spending, and it estimates that the debt rule relaxation could generate an additional €650 billion over a four-year period. The politics of the math are instructive: €650 billion + €150 billion = €800 billion. This is an amount not too dissimilar to what the US spends on defence in a year, and the projected four-year horizon conveniently matches US presidential terms. The figure of €650 billion does not exist today, even if it can be conveniently mobilised for short-term political ends.

More concerning, however, is that the national escape clause under the SGP is no guarantee that defence spending will be increased uniformly across the EU. Germany’s revision of national debt rules and its subsequent announcement of a €500 billion injection of investment infrastructure and defence, already represents a huge part of the €650 billion target. There is also a questionable dimension to the use of the national escape clause for defence. It enables more national defence spending without any guarantee of cross-border investments in the EU, so the risks of duplication and fragmentation could persist. This reinforced fragmentation could lead to much lower competitiveness in the EU defence sector, the crowding-out of SMEs and start-ups and the creation of fewer and fewer “national champions” that do not operate on a European scale. What is more, additional national defence spending in this way may not always result in the most relevant areas of defence investment (i.e. the balance between equipment investments, innovation, personnel, pensions, infrastructure, etc). Finally, the additional investment under this initiative could even be spent on non-EU supplies of defence systems and equipment – a development that would clearly contradict the Commission’s own objectives. Perhaps the NEC initiative is being used to entice member states into agreeing to other EU proposals such as SAFE and the EDIP, but this is a risky bet if both of these initiatives are significantly watered-down by member states.

Yet, in other areas of the White Paper, the proposed initiatives hold more potential for genuine EU defence cooperation. For example, the Commission is proposing to utilise unspent funds under cohesion and regional development policy for defence. As part of the mid-term review of the Multi-annual Financial Framework (MFF), the Commission will allow member states to reprogramme funds for defence (e.g. infrastructure, military mobility and production). This means that it will be easier to pre-finance the most pressing military needs in critical geographical areas in the EU (e.g. the Eastern border regions and states). Another proposal that will lead to genuine pan-European efforts is to continue to adapt the European Investment Bank (EIB) for defence. The Bank not only intends to increase its yearly investment in drones, space, cybersecurity, quantum technologies, civil protection and military facilities, but it is also exploring a further revision of its loan eligibility criteria – which presently excludes defence proper (i.e. military capabilities) – to better serve European defence. Finally, the White Paper’s stress on mobilising private capital for defence could be an invaluable additional source of investment for SMEs and Mid-Caps.

And, finally, we cannot neglect the proposed “European Defence Industry Programme”, which could see the EU support – for the first time – common defence procurement projects. While the EDIP is foreseen to have a budget of €1.5 billion up to 2027, there is no clarity on how big the EDIP should be after this point. Some have called for a figure of €100 billion. The final amount will depend on member states, and it is for this reason that the EDIP is perhaps the most contentious EU defence initiative of all. Aside from it being grant-based, EDIP would be the only EU programme designed to help develop common defence capabilities. Money would only be released to member states from the EDIP on condition that groups of states work together to develop military capabilities. Additionally, by moving the EU into the business of common development and procurement it will be possible to address structural issues facing the EDTIB such as security of supply. Given its high potential, however, the EDIP is most at risk from the member states and national reflexes. If member states want to cool the potential relevance of the EDIP, they will push for a minimal amount of investment in the programme. This move would be entirely at odds with the present geopolitical climate, but it is not a given that member states will agree to an ambitious financial envelope.

Some member states might come under significant pressure to force open the EDIP to participation by third states such as the US or the United Kingdom (UK). Knowing how difficult – if impossible – this would be in practice without spoiling the EU’s security of information and technology control rules, the argument would shortly follow that in order to limit the political fall-out from excluding such third states it would be wise to lower the overall financial commitment to EDIP. The same strategy played out during the EDF negotiations, when the Fund was reduced to €8 billion from an initial request for €13 billion by the Commission, following concerns that the Fund would negatively affect relations with the first Trump administration. And here too, certain member states with strong defence industrial links to the US and UK will be most alert to these sorts of tactics.

Let us also not forget that the amount dedicated to the EDIP after 2027 would be contingent upon the MFF negotiations, where other policy areas would vie for prioritisation. If member states deem the EDIP a step too far down the road of EU defence integration, they may well use the wider MFF negotiations to stymie the potential of EDIP. And even beyond the overall financial package for EDIP, the content of the proposed regulation is under careful scrutiny. We have already experienced divisions in ongoing negotiations for EDIP that have centred on how far to allow access to non-EU industries to questions about the Commission’s proposed governance of the EDIP. In this respect, the EDIP would grant the Commission a greater say in capability development in Europe. The inclusion of ideas such as a Defence Readiness Board or European Military Sales Mechanism in the proposed regulation has certainly spiked member states’ interest.

Conclusions

Even though European security and the transatlantic relationship are in disarray, EU member states are still hesitant about defence integration. Most member states will seek to weather the transatlantic storm over the next four years, with the hope that the next US president will revert to some kind of status quo in European security. However, they also fear that greater EU defence integration could entail an irrevocable – and permanent – structural change to the EDTIB. They fear that measures taken today in the Union could, if mishandled, effectively lead to an anti-competitive defence market put in the hands of a few national champions. They fear that any use of EU funds to this end could essentially lead to indirect subsidisation for only a few companies and European states. Some of these fears are genuine, but they are often times articulated in bombastic ways. Hence the repeated cries of Commission “power grabs” or of a need to cull some mythical political beast vaguely called “Brussels”.

The truth of the matter is that the Commission can only propose initiatives. The Commission cannot forcibly drag member states to a place they do not want to go. Yet member states are over-stating their case against deeper EU defence integration. They recognise that there are limits to what can be achieved through NATO, but at the same time they are under immense pressure to defend Europe – potentially without their long-standing security guarantor. Something has to give. And, in the coming months, if what gives is European security then member states will have no option but to “think big” – if, indeed, they are still in a position to do so. In this sense, it is better for member states to get ahead of the curve and to structure EU defence in an effective, equitable and sustainable way rather than have catastrophic events or the (social) media cycle shape their actions.

__________

The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for Security, Diplomacy and Strategy (CSDS) or the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB).

ISSN (online): 2983-466X