CSDS POLICY BRIEF • 24/2024

By Daniel Fiott

3.9.2024

Key issues

- Given the geopolitical outlook for Europe, security of supply is a necessary element of enhancing the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB) and ensuring industrial readiness and strategic autonomy.

- The European Commission has proposed a security of supply regime, not least to overcome market fragmentation. A key challenge will be overcoming the voluntary nature of past security of supply initiatives and managing EU member state interests.

- Security of supply in the EU can be achieved through the creation of a genuine Single Market in defence, more effective contracting, stockpiling, investment screening and defence partnerships.

Introduction

Following the experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic and the need to surge defence production in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the issue of security of supply has become a pressing feature of the European Union’s efforts to enhance defence readiness. In the Versailles Declaration of March 2022, for example, leaders tasked the European Commission and European Defence Agency (EDA) to draw up a defence investment gap analysis. This, in turn, lead to the realisation that critical dependencies and bottlenecks could drastically affect European defence in times of crisis. In March 2024, security of supply was more directly addressed in the European Defence Industrial Strategy (EDIS), which made clear that security of supply is a core pillar of EU efforts to ensure that member states ‘invest more, better, together and European’. The EDIS argued that supply chains are still largely organised on a national basis in the EU, which can create supply risks in times of crisis and geopolitical uncertainty. It went on to remark that the over-reliance on third country supplies, combined with a lack of a Single Market at the higher tiers of defence production, means that the EU risks facing potentially harmful dependencies and hindrances to its freedom of action. All of these factors play into the rationale for the creation of a security of supply regime at the EU level.

Yet, security of supply is a complicated matter fraught with political sensitivities, especially when organised across borders. In fact, for the EU security of supply is not a new issue, but past initiatives have proven ineffective due to reservations by EU member states and industry. Such reservations partly centre on sensitivities about sharing commercial/security information, and a suspicion that EU-level initiatives may lead to a creeping communitarianisation that may undermine national security of supply initiatives. Still, in a context where the Commission is preparing a White Paper and awaiting the “Draghi” and “Niinistö” Reports, it is worthwhile asking whether a more EU-level approach to security of supply can add value in times a crisis. The purpose of this CSDS Policy Brief is to unpack the meaning of security of supply, reflect on the proposed security of supply regime proposed by the European Commission and consider some of pressing policy issues that may need to be addressed sooner rather than later.

The challenge of defining “security of supply”

In 2016, the European Commission produced a Guidance Note on Security of Supply to outline in more detail security of supply considerations under the Defence Procurement Directive (2009/81/EC). In the Guidance Note, the Commission defined security of supply ‘as a guarantee of supply of goods and services sufficient for a Member State to discharge its defence and security commitments in accordance with its foreign and security policy requirements’. This definition still holds true in the present context, although how we consider the term “sufficient” for an EU member state to discharge their commitments has greatly changed. Indeed, ever since the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 there is a greater need to improve the “sufficiency” referred to in the 2016 Guidance Note on Security of Supply.

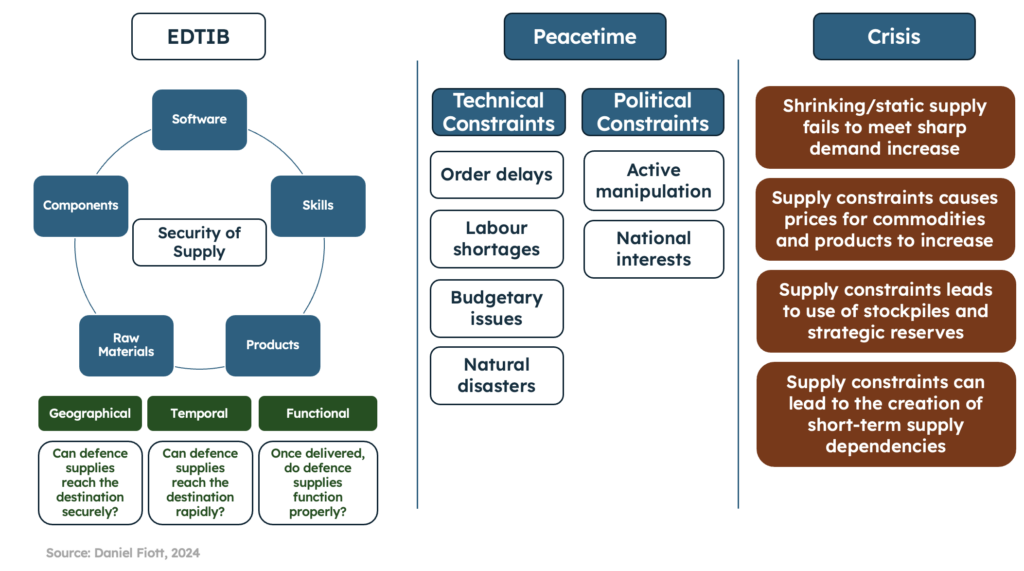

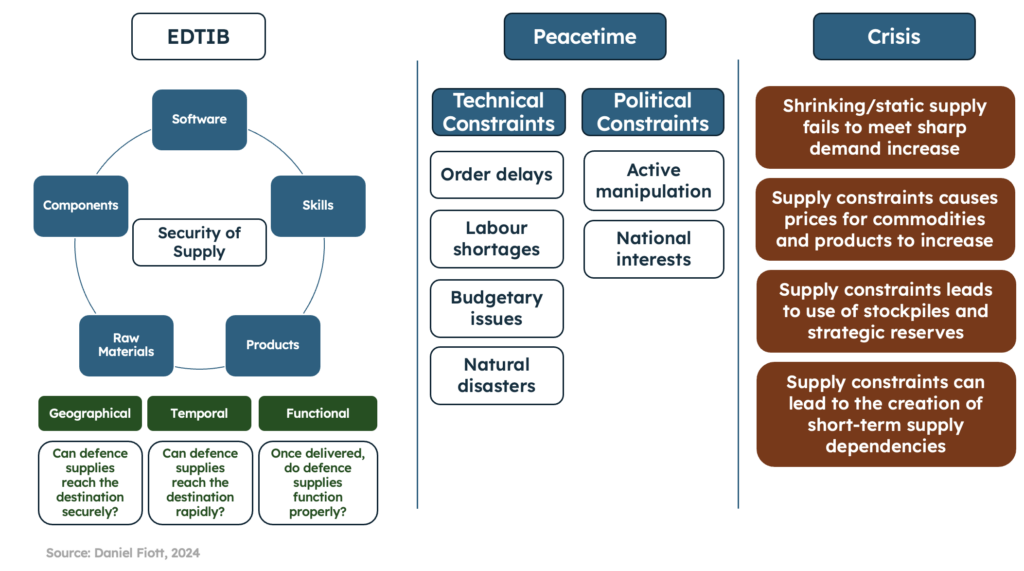

Security of supply considerations are evidently more acute during times of crisis. In essence, security of supply refers to the production and maintenance of military equipment, which in turn relates to components, spare parts and even software related items. The aim is to ensure that systems, components and technologies are delivered in such a way as to allow governments to fully exercise their defence and security policy – in other words, to avoid undue foreign political interference in the conduct of national defence. In this respect, security of supply has geographical, temporal and functional dimensions: 1) supplies must physically reach a particular geographical destination; 2) they must reach a destination in a timely fashion; and 3) once supplied they must meet basic functional/performance requirements.

Despite these reflections, however, defining “Security of Supply” in defence can be challenging, not least because we have to ultimately assess who is responsible or best-placed to manage supply chains. Although governments clearly have a political responsibility to ensure that armed forces are supplied with military equipment and supplies, the reality is that firms themselves manage vast networks of suppliers and this places firms on the frontlines of assessing potential supply restrictions or bottlenecks. For example, Airbus maintains approximately 8,000 direct and 18,000 indirect suppliers from more than 100 countries across the globe. Such companies have designed their own methods of ensuring SoS, not least through contracting and the used of standards. What is more, there is a need to better understand the mix of (EU and non-EU) public and private ownership of firms supplying the European market. One study has already calculated that some 25-30% of the EU’s largest defence firms are subject to non-EU ownership.

There is also some debate about the nature of “risk” in security of supply. While supply blockages or restrictions are damaging for defence production, it is perhaps fruitful to distinguish between blockages or restrictions for “technical” market reasons (i.e. order delays, budgetary issues, labour shortages, natural disasters, etc.), on the one hand, and “political” reasons (i.e. active manipulation of supply or a political decision to favour domestic supplies over exports), on the other. Each of these types of risk require specific mitigation or adaptation strategies. For example, a great number of European airforces have procured the F-35 fighter aircraft from the US. While it can be argued that the decision to procure this aircraft is based on performance and interoperability, it still represents a form of dependency that is affected by US production capacities, budgetary bandwidth and domestic/foreign politics. The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) has frequently stated in relation to the F-35 that, ‘contractors continue to deliver engines and aircraft late – a trend that has worsened in the last few years’. This appears to be a “risk” that several European airforces are comfortable assuming.

Figure 1 – An overview of security of supply

Associated with the difficulty of defining “risk” is also the challenge of defining “crisis” in terms of security of supply. Most would agree that the current war on Ukraine poses a crisis situation, which, as we have seen, has already given rise to supply shortages (e.g. ammunition). Yet, the reality is that the war on Ukraine is still not felt as an acute crisis for many European states (especially in Western and Southern Europe). In this respect, there is potentially a need to test specific military or crisis scenarios against the capacity of the defence sector to produce or supply critical products and services. For example, should the United States become locked in a war in the Indo-Pacific there would be inevitable supply shortages that would directly impact Europeans as they seek to deter Russia. We have been here before in history, as shortages of US-made ammunition during the Korean War partly contributed to ammunition supply shortages in Europe during the 1950s.

Additionally, defining security of supply can be challenging because the potential areas where a lack of security of supply may occur are numerous and fall across the full life-cycle of equipment and systems production and acquisition. Therefore, supply chain insecurity may apply to the maintenance of military systems and equipment as much as it does to the production of them. In this sense, there is a need to scope out the most vulnerable parts of the life-cycle of defence systems from a security of supply perspective. It is also worth underlining that supply and cost are intimately linked: a lack of supply for defence products will result in higher prices. There were reports from the recent past that in the European naval sector steel witnessed a 40-60% price increase – with steel and aluminium making up 60% of the total costs of small ships.

Lastly, the labels of “foreign supplier” or “third state supplier” are arguably contested terms. In most cases, to determine the level of dependency (and potential harm) for equipment, components and/or technologies we must analyse the ultimate ownership of firms. This is further complicated because a majority of firms in the defence supply chain are privately owned, and in many cases they are commercial firms operating in the open market. In some cases, such as with China, the link between private and public firms is extremely blurred, raising questions about the suitability of dependencies on Chinese supply chains and/or companies. In other cases, however, third country industries have established themselves in the EU including by employing European labour, establishing head offices and creating lobby groups (e.g. AmCham).

European responses

Russia’s war on Ukraine has certainly shifted greater attention towards the issue of security of supply, both in the EU and NATO. While NATO recently endorsed a “Defence Critical Supply Chain Security Roadmap” to ensure that Allied countries can avoid supply disruptions, it is in the EU where a range of security of supply initiatives already exist. However, the effectiveness of these measures remains underwhelming. True, initiatives such as the Critical Raw Materials Act will help the defence sector (albeit indirectly), but past security of supply initiatives have been found wanting. For example, the Defence Procurement and Transfer Directives and a range of EDA voluntary measures and initiatives have sought to take down barriers to supply and identify supply bottlenecks. As the European Commission’s 2016 evaluation of the Transfers Directive states, however, ‘the Directive had a minor positive effect on the security of supply of defence-related products’.

The difficulties of designing a suitable and effective security of supply regime at the EU level are familiar. As the EDIS makes clear, the fragmentation of supply chains along national lines in the EU is not conducive to ensuring EU-wide security of supply. While support for national supply chains may help protect national industries, there is a risk that this may create cross-border supply risks as well as increase the costs of maintaining largely national supply chains. However, the flip-side of this argument is that national governments are extremely reluctant to engage in an EU-level regime on security of supply because the see “defence supply” as a core component of national security and national industrial interests. This fact continues to make any planned security of supply regime at the EU level very difficult. Nonetheless, despite these difficulties there is still a willingness on the part of the European Commission to develop a legal framework for security of supply.

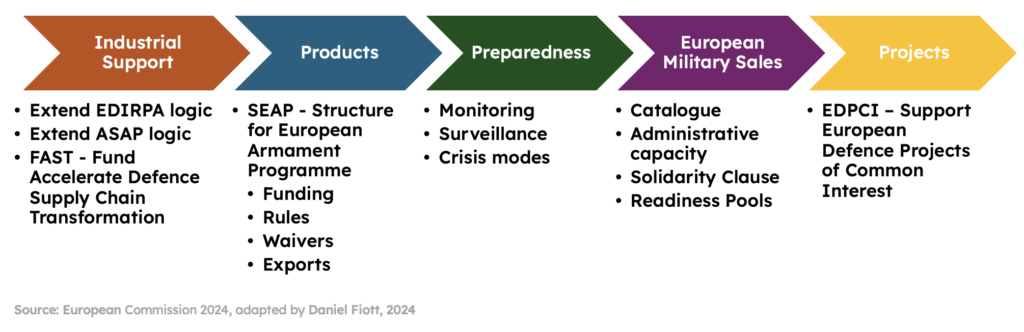

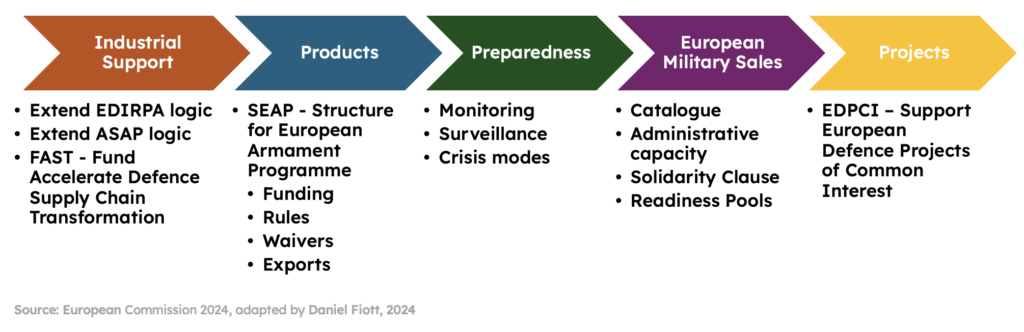

Figure 2 – the Commission’s preferred regime

In its Staff Working Document on the European Defence Industry Programme (EDIP) of July 2024, the European Commission argues that security of supply applies to raw materials, components, goods and finished defence products. Interestingly, the Commission argues that there is a lack of clarity on the defence security of supply outlook in the EU, and they raise the point that national independence is increasingly difficult as ‘fewer supply chains are under the control of a single Member State’ due to the intricacy of supply chains and the complexity of state-of-the-art capabilities. What is clear from the Commission’s analysis is that the EU and its member states have only a rudimentary understanding of the supply chains supporting the EDTIB.

There is even less clarity over how these supply chains would function in a period of crisis, or how member states would coordinate security of supply actions in such times – the Commission refers to this as ‘a clear legal vacuum’. Here, it is worth noting that under the EU Treaties member states have undertaken to aid each other in times of crisis through mutual assistance and solidarity. Any major crisis in the EU that would lead to the triggering of these clauses would more than likely involve member states demonstrating solidarity with each other through the delivery of weapons or ammunition, among other responses. Even if NATO’s Article 5 is the key response to a major crisis or war, it is inconceivable to think that the EU would not at some point be involved in the response. In this sense, there is an inconsistency between EU treaty-based security guarantees and an EU security of supply framework.

Given this “legal vacuum” at the EU level, the EDIS calls for a security of supply regime based on: 1) a “crisis state” mechanism to trigger crisis response initiatives to ensure the priority supply of critical components and raw materials; 2) the stockpiling of basic components, technologies and raw materials; 3) greater monitoring of dependencies and bottlenecks via the EU Observatory of Critical Technologies and the creation of new bodies such as the Defence Industrial Readiness Board and a European Defence Industry Group; 4) financial support to stimulate the supply chain (e.g. the FAST Fund) and 5) the cross-sectoral fertilisation of efforts between defence and other tech areas (e.g. semiconductors).

The Commission’s Staff Working Document goes further in outlining an security of supply regime that would seek to address most areas of the defence life-cycle through a mixture of 1) industrial support; 2) products; 3) preparedness; 4) European Military Sales; and 5) projects (see Figure 2). In terms of industrial support, the Commission proposes that the EU extend the logic of the European Defence Industry Through Reinforcement through Common Procurement Act (EDIRPA) and the Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP) to provide financial support to boost aggregate defence orders. This support should come in conjunction to the proposal for the Fund to Accelerate Defence Supply Chain Transformation (FAST). For products, the proposed Structure for European Armament Programme (SEAP) would see a blend of funding, rules, waivers and support for the development of defence products. For preparedness, the Commission proposes to increase surveillance and monitoring of bottlenecks and potential shocks. European Military Sales foresee the creation of a supply catalogue, administrative support, greater solidarity and readiness pools. Finally, projects relates to the desire to create common European defence projects to boost production and support the EDTIB.

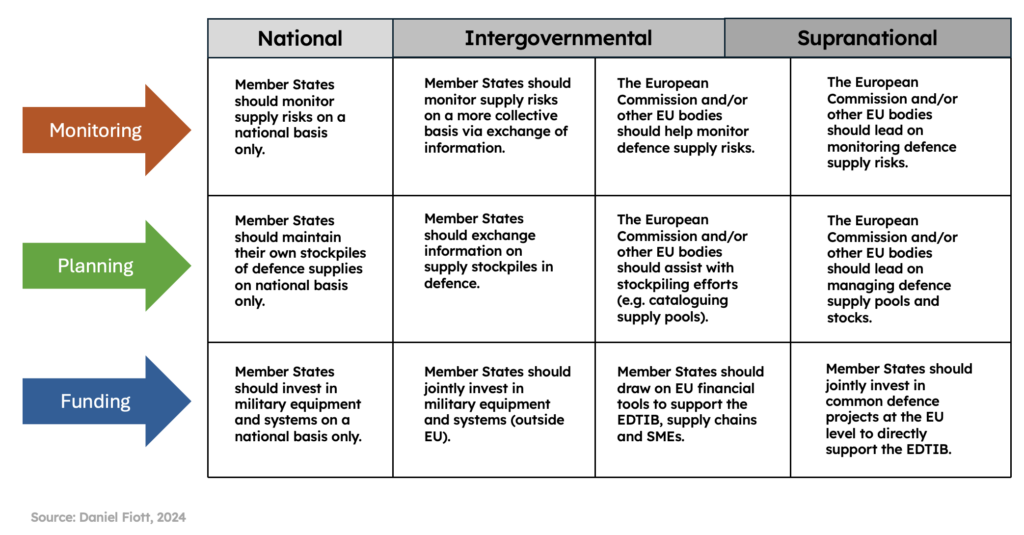

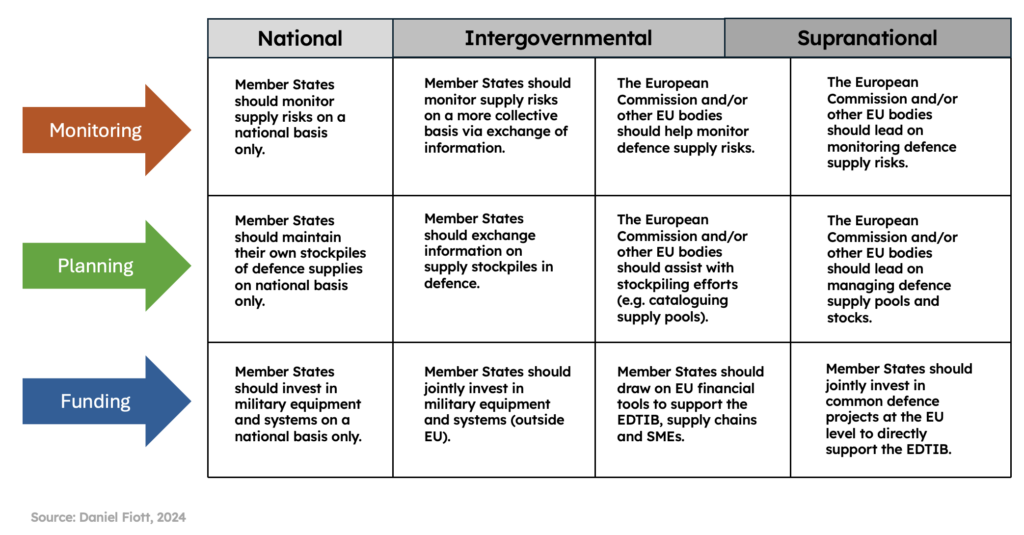

Such a proposed security of supply regime actually expands upon the stipulations of the proposed Regulation for the EDIP, where (see Chapter V, Article 57.5 and 57.6) security of supply measures in times of crisis are defined in terms of information exchange, coordination, guidance and crisis measure reviews via the proposed Defence Industrial Readiness Board. Such measures can only ever form part of a partial approach to security of supply. There is, therefore, a need to reflect on how best to understand what an EU Security of Supply regime could look like in practice by providing options for governance (i.e. national, intergovernmental, supranational). However, the scholarly work shows how there is no direct EU competence for security of supply. The EU Treaties specifically state that national security remains the sole responsibility of member states (Article 4.2 TEU), which means that security of supply is subject to national control.

Figure 3 – Managing security of supply

The one major exception to this legal context is Article 114 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU), which refers to the establishment and functioning of the internal market as laid down in Article 26.1 TFEU. However, while Article 114 TFEU is relatively broad in scope it is limited to the adoption of legal acts (Regulations and/or Directives) that aim to harmonise the internal market in specific sectors or to remove obstacles, assuming that obstacles exist. In this respect, the need to ensure the proper functioning of the internal market in the defence sector runs into national security concerns that could be justified under Article 346 TFEU. This balance, between national security and market harmonisation, is at the heart of debates about security of supply. However, this balance raises questions about the most effective mode of governance for security of supply, and how best to balance national, intergovernmental and supranational approaches.

As Figure 3 shows, there are various aspects to security of supply that could be considered at the EU level, but there are political implications for each type of governance: national, intergovernmental or supranational. If security of supply is broadly categorised in terms of monitoring, planning and funding, each aspect can be governed by national, intergovernmental and supranational methods of governance. Under national approaches, the EU is not involved at all but then neither are NATO or any other minilateral or regional formats. Intergovernmental modes of governance opens the door to the EU and other non-EU formats, and this can rest on the exchange of information, the creation of stockpiles or joint investments in capabilities. Finally, a supranational method of governance would more heavily involve the EU institutions with member states working together for monitoring, planning and funding purposes through a more centralised process.

Options for Europe?

In thinking through any possible security of supply regime at the EU level, it is first necessary to recognise that measurestaken at the EU level without a specific or direct security of supply dimension can still contribute to security of supply. For example, funding common defence projects can strengthen the EDTIB, which in turn can help ensure security of supply. In this respect, even if member states do not settle on a formal security of supply regime at the EU level, the issue of security of supply will not go away. In fact, more can be done to ensure that the Single Market responds to the need to ensure cross-border defence supplies in times of crisis. There are still too many barriers to cross-border cooperation and transfers for defence in the EU. This is not a new feature of the security of supply debate, but existing legal instruments are clearly not breaking down barriers to supply. In times of crisis, there is no EU mechanism to enforce cross-border supplies of defence equipment. The EU Defence Procurement and Transfer Directives have limits, so national fragmentation persists within the EU. Yet, the creation of a Single Market in defence does not only depend on legislation, as the financing of common defence projects offers an opportunity to build industrial scale in Europe while also ensuring secure supply chains.

Another feature of security of supply that can be considered outside of any formal regime relates to contracting and diversification. Contracts will remain the main legal instrument to manage risk and ensure supply, especially during peacetime. There is already extensive experience of including security of supply needs in the award criteria of defence systems and product contracts. Industry bears a lot of responsibility in this respect, but the idea that governments (also via the EU) can work to enhance contract guidelines on security of supply should not be overlooked. This is especially relevant given that prime firms maintain extensive, global, supply chains. In Japan, for example, the recent Economic Security Promotion Act (2022) – while not specifically focused on defence – has pushed the barriers on enhancing corporate responsibility for ensuring supply. Any attempt to address contracting requirements in security of supply could be raised within the potential future structures such as the Defence Industrial Readiness Board and the European Defence Industry Group.

It should also be noted that supply diversification and the incentivisation of new defence market entrants can play a role in managing supply. For example, given the constraints facing the US DTIB academics have suggested that the US government revert to a process adhered to during the Cold War of “second sourcing”. This entails awarding dual contracts for products (to at least two firms) over a period of time, with the idea that overall production is increased, but in line with greater performance and more competitive prices. Australia, for example, has started to experiment with electronic applications to boost defence suppliers, with downloadable smart apps designed to encourage firms (hitherto not in the defence sector) to start supplying goods to the Australian government via its Australian Defence Export Office portal and downloadable Defence Export Catalogue.

Yet, supply diversification can only work in cases where there is an abundance of supply and this strategy is less effective in cases where supplies are rare. For example, the 2023 study on critical raw materials for the EU identified gallium, germanium, lithium, tungsten and more as being of high criticality for the Union. In this regard, one of the other key policy options that has emerged in recent times relates to strategic reserves or stockpiling. Again, individual member states may have their own national plans for stockpiling strategic resources, but there is no overarching EU approach and this weakens the Union’s overall ability to monitor and prepare for supply shocks. Having in place an overarching stockpiling register or record could also assist policymakers in scoping out the exact location of stockpiles and how easily accessible they can be in times of crisis. Relatedly, in time the EU could consider whether budgetary support for maintaining strategic reserves is worthwhile. As we have learned with military mobility, there are costs involved in modernising and maintaining infrastructure, so plausibly the EU could provide financial support for storing critical defence supplies.

Aside from stockpiling, the EU can already utilise existing policy mechanisms such as the Investment Screening Mechanism with a greater focus on defence supply. As demand for defence equipment and systems is increasing on a global basis, there is an additional risk that non-EU firms engage in mergers and acquisitions with EU-based firms (“buying up capacity”) to meet short-term demand spikes. This means that existing capacity can be re-directed or mobilised without the overall production capacity being increased. This process implies a need to focus efforts on the screening of foreign direct investment in order to ensure that EU-based firms and capacities are not owned by third states that entail risks for security of supply in defence. In some countries, this risk is mitigated by ensuring that supply contracts stipulate a need to notify governments in case of a change of ownership, which may in turn trigger a due diligence and risk assessment process.

Finally, there is a need to help offset the growing problem of supply prioritisation on the global defence market. “Waiting in line” for foreign defence supplies or systems is becoming more of a global political issue, especially in a context where non-EU suppliers face difficulties in their national DTIBs. For example, there is increasing attention on the US DTIB and its ability to produce equipment and materiel in a timely fashion and at scale. Interestingly, for countries such as the US there has been an increased attention to striking up bilateral security of supply arrangements. The US currently has 18 such arrangements in place, 9 of which were signed in just the last two years. In its most recent arrangement with India, the US and India pledge to provide “assurances” of a voluntary nature ‘to make every reasonable effort’ to provide reciprocal priority support for military supplies. In a geostrategic context were the supply of defence equipment and components is even more vital, these types of bilateral agreements will become more common place.

In this respect, the EU has already signed several sectoral bilateral agreements with close partners in areas such as digital trade, critical raw materials and security. The EDA has also signed Administrative Arrangements with key partners that include dialogue on supply chain issues. Nevertheless, as part of the EU’s international defence diplomacy the Union could explore the possibility of signing bilateral reciprocal defence supply agreements with close partners. Although the majority of existing supply arrangements are voluntary in nature, the EU could use such bilateral agreements to enhance transparency between partners on supply vulnerabilities, stockpiles and more. In many respects, integrating a defence supply perspective into existing trade partnerships should also be considered, especially in dual-use technology areas. However, it will be extremely difficult for the EU to engage in such bilateral agreements without its own coherent security of supply regime.

Conclusion

Part of the ongoing discussions to enhance Europe’s defence readiness increasingly includes security of supply. This is natural given that security of supply is a critical feature of military power and political autonomy. The shifting geopolitical context makes it even more necessary to reflect on the best way to ensure security of supply in the EU. Russia’s war on Ukraine has exposed Europe’s production shortfalls, and there was no clear defence industrial strategy to prepare Europe’s defence industry for the war. In this respect, ensuring security of supply in defence is also an important feature of credibility, preparedness and deterrence. In this context, it is understandable to see why the European Commission is arguing in favour of an EU security of supply regime. Part of this proposal centres on greater EU involvement in monitoring and surveillance, but the reality is that – even if a good start – monitoring is not enough alone. Without the other dimensions of security of supply such as financing, common defence projects or regulations it will be difficult to create a genuine security of supply framework. Whatever regime or initiative emerges over the coming months, it is clear that the issue of security of supply will remain an essential feature of European defence.

__________

The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for Security, Diplomacy and Strategy (CSDS) or the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB).

ISSN (online): 2983-466X