CSDS POLICY BRIEF • 11/2025

By Martin Chorzempa and Lukas Spielberger

6.5.2025

Key issues

- The international financial system remains centred on Western currencies and financial infrastructures, but there are concerns about the dollar’s dominance.

- China has promoted internationalisation of the renminbi with multiple strategies that have partially borne fruit, but it is not a serious contender for a leading international currency.

- US and European policymakers should consider countering or attenuating China’s efforts to use its currency for bilateral foreign policy.

Introduction

Despite warnings for over a decade that the United States (US) dollar’s pre-eminence could fade into a more multipolar international currency order that includes the Chinese renminbi, the international financial system remains centred on Western currencies and financial infrastructures. By any measure of a currency – medium of exchange, store of value and unit of account – the dollar widely leads other currencies. As of March 2025, the dollar share was 47% of global payments, followed by the euro at 22% (the renminbi is fourth at 4.7%). Over half of all official foreign exchange reserves are in dollars. Far more world trade is invoiced in dollars than the US share of exports. Meanwhile, the global standard for payments between banks outside of Russia is the Belgium-based Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) network, no matter the currency.

The US dollar remains dominant in the global economy not because of any formal mandate, but because of the decentralised decisions of countless traders, exporters, importers and financiers. Powerful network effects reinforce its dominance: the more widely the dollar is used, the more beneficial it becomes for others to use it too. Most of the world’s trade is invoiced and settled in dollars, and a large share of global finance is conducted in dollars as well. This widespread use increases demand for dollar-denominated assets and for access to US-based payment systems, which are often cheaper and more reliable than alternatives because they are so liquid. As a result, the dollar is more convenient and less risky to use than other currencies. This self-reinforcing cycle brings major advantages to the US, including lower borrowing costs, higher asset prices and safe-haven status during global crises. Even China’s Belt and Road Initiative often relies on dollar-denominated lending rather than the renminbi.

Yet recent headwinds related to policy predictability, Federal Reserve independence and the fiscal situation, among other issues, are adding to longstanding concerns about US dollar dominance that could benefit China. For years, countries and firms have explored alternatives that would insulate them from US influence and sanctions, though so far with limited success. Former US Treasury Secretary, Jack Lew, has argued that increasing “weaponisation” of Western-based financial infrastructures risks “sanctions overreach” that creates incentives to de-dollarise for countries that might be on the receiving end. The powers the dollar bestows on the US have sometimes been a source of even transatlantic tension. Disunity was at its height when re-imposition of sanctions during the first Trump administration forced Europeans (and SWIFT) to cut ties with Iran and led to failed European attempts to work around the dollar. At other times, dollar sanctions contributed to European security as part of a unified front against Russia in 2022. Despite a commitment to strengthen the international role of the euro, European Union (EU) policymakers have not matched China’s attempts at currency promotion.

Concerned it may one day be on the receiving end of sanctions, China hoped to erode the US’ leverage over Chinese trade in goods, services and finance not only with the United States, but with much of the world. Beijing has promoted internationalisation of the renminbi with strategies that include partial liberalisation of capital flows, promotion of central bank swap lines, creation of parallel payment systems and a digital currency. It has also ordered state-owned companies to boost the renminbi use in cross-border activity. Beijing’s efforts have borne fruit: between 2016 and 2022 the renminbi nearly doubled, going from one side of 4% of global transactions trading one currency for another to 7%, but that rise has come at the expense of other currencies. The dollar’s dominance, on 88% of such transactions, is untouched.

If China were in a position to capitalise on the dollar’s woes to usher in a new multipolar currency order with a prime role for the renminbi, the economic and geopolitical ramifications would be profound. For one, the US, the EU and other allies may lose some of their sanctions’ bite, as sanctioned countries could transition away from the dollar or euro to adopt the renminbi. Other nations might bow to China’s increased financial power in various ways to avoid being shut-off from the renminbi needed for trade. As an historical precedent, the dollar’s rise to international currency status was similarly transformative.

Yet even with worldwide concerns about the dollar, the renminbi is not yet ready to be a serious contender for leading international currency status. This Policy Brief examines three of the most important Chinese approaches to increasing the renminbi’s role as an international settlement currency and finds that Beijing’s efforts fall short of posing a systemic challenge to the dollar or to infrastructures like SWIFT. Nevertheless, they have enabled China to use its currency for bilateral foreign policy. US and European policymakers should consider countering or attenuating these efforts, even though they have had limited success in increasing renminbi usage.

Chinese financial statecraft and the international financial system

For over 15 years, Chinese policymakers have stated their ambition to internationalise the renminbi and potentially rival the dollar. People’s Bank of China (PBoC) policymakers first argued in 2006 that ‘the time has come for promotion of the internationalisation of the yuan’. Motivations for this policy ranged from economic objectives such as increased competitiveness to ‘enhanc[ing] China’s international status’ and a ‘rise in power standing’. Although the 2008 global financial crisis made clear that excessive reliance on the dollar brought economic risks, the internationalisation of the renminbi was also seen as a geopolitical project from the beginning.

Although China became the world’s largest exporter in 2009 and the second largest economy in 2011, international usage of the renminbi underperforms China’s economic heft. While dollars and euros already circulated widely as international currencies, the renminbi could mostly be used only for trade with China, and unlike the dollar and the euro, the renminbi was not freely usable due to controls on capital flows in and out of China. Trying to loosen these controls and be more competitive with incumbent currencies proved tricky after currency and stock market instability in 2015 revealed the fragility of Chinese financial markets and temporarily halted renminbi internationalisation. After more than a decade of Chinese currency promotion, in 2023 the renminbi became the fourth-most widely used currency for international payments and overtook the euro to be the world’s second-most used currency in trade finance. Pressure on the renminbi from US tariffs led China to tighten controls further, underscoring its emphasis on domestic stability over the convertibility that would be needed to present an alternative to the dollar.

Rather than rely on market forces alone, the Chinese government has resorted to active policy measures to promote its currency. Its efforts can be considered “financial statecraft”, a ‘national government’s use of monetary or financial regulations or policies to achieve foreign policy ends’.

The Chinese approach has revolved around a two-track strategy. First, it has sought to foster the renminbi’s role as an international store of value by promoting offshore renminbi holdings – notably by supporting Hong Kong as a financial center. Second, it aimed to increase the renminbi’s role as an international means of payment through three strategies this Policy Brief focuses on. One has been to promote bilateral swap agreements between the PBoC and other central banks. The second has been to create international payment systems that do not involve the dollar, most notably the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System – CIPS. Third, China has been developing a central bank digital currency – CBDC – for alternative payment infrastructures.

To appraise the impact of these policy initiatives, it is important to set expectations. Currency competition is not a matter of exclusive dominance; most jurisdictions will continue to engage with both Western and emerging Chinese financial infrastructures. What matters is the relative importance that China can play within international financial networks and its ability to offer an alternative to the dollar. Moreover, even if the systemic impact of Chinese financial statecraft remains limited, the relative size of many countries’ direct trade with China and their need for external financing may still allow Chinese financial statecraft to make a difference at the bilateral level. Chinese currency promotion may be more significant than market shares suggest.

Increasing renminbi attractiveness through swap lines

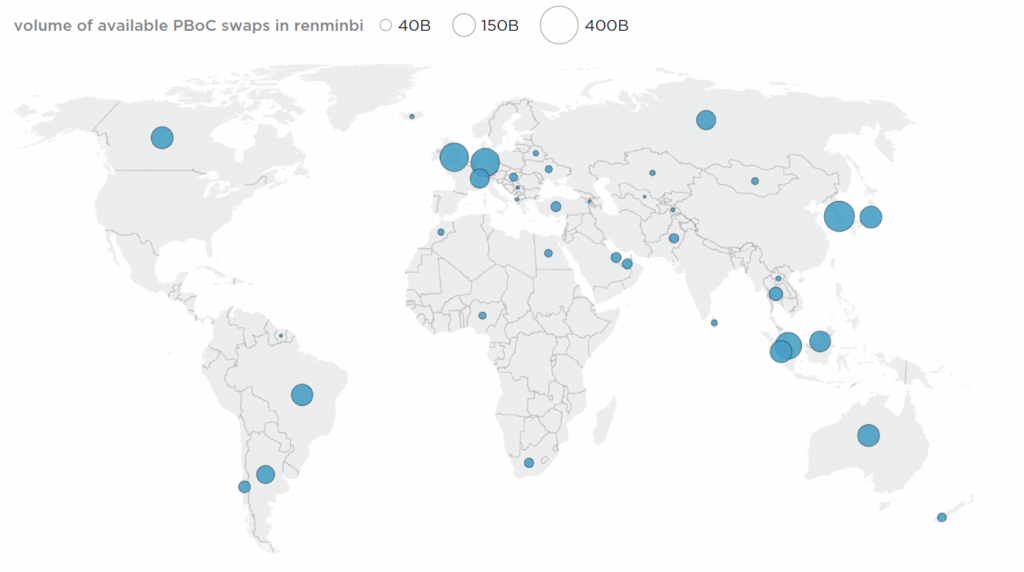

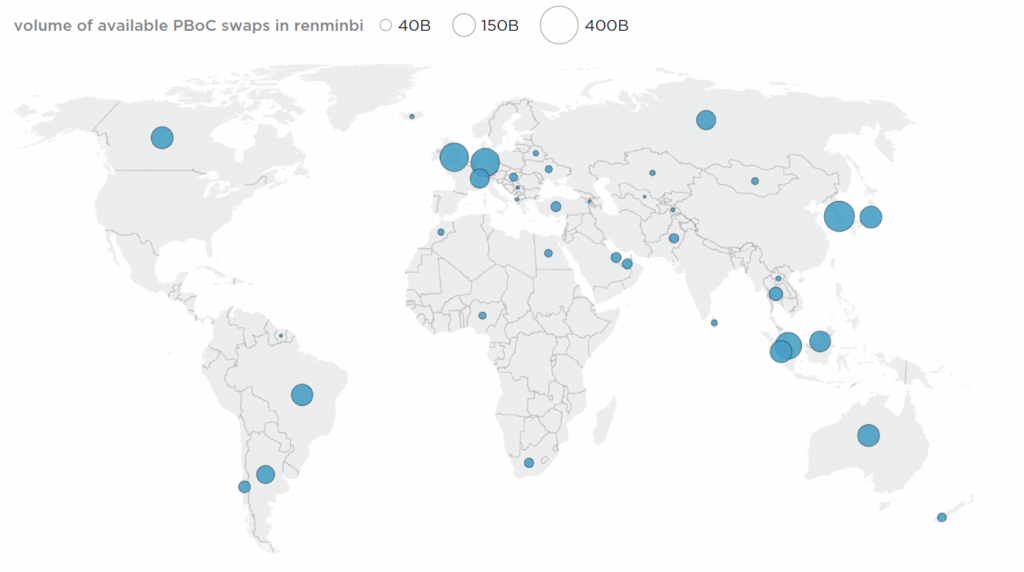

In 2008, the PBoC opened its first bilateral swap line with the Bank of Korea. Scholars at the Council on Foreign Relations estimate 40 credit lines with other central banks have followed, which could draw on a combined total of over half a trillion dollars. This tool would seem to place the PBoC ideally to promote renminbi usage. Figure 1 shows PBoC’s bilateral currency swap lines as of 2021.

Figure 1: People’s Bank of China’s bilateral currency swap lines, as of 2021

Note: Size of bubbles represent the maximum amount that can be drawn in billions of renminbi.

Source: Horn et al. (2023), PIIE

Operationally, the PBoC’s credit lines resemble swap lines that the European Central Bank (ECB) and, most notably, the Fed have set up since the global financial crisis. The lending central bank extends a loan in its own currency, which is secured against the currency of the borrower. Yet the intention and usage of Chinese and Western swap lines differ.

The Fed and the ECB maintain swap lines with few systemically relevant central banks that can be used to respond to international liquidity shortages in dollars and euros, respectively. The Federal Reserve extendednearly US$600 billion in credit through these facilities during the 2007-2009 financial crisis and provided close to US$500 billion during the early 2020 market turmoil linked to the pandemic. The ECB’s credit lines were smaller but still helpful for countries in the EU’s periphery.

Chinese swaps were initially intended to support the renminbi’s role in trade invoicing. If an importer in, say, Malaysia wanted to buy Chinese widgets in renminbi, the Central Bank of Malaysia would be able to furnish renminbi against the Malaysian ringgit to settle the trade. However, this usage of PBoC swaps never took off, as political economist Daniel McDowell argued in 2019, and many credit lines have sat unused.

However, PBoC swaps proved useful in individual cases, notably Russia, which has repeatedly used its swap as it shifted to renminbi-denominated trading following Western sanctions in 2015. Since some major Russian institutions were excluded from SWIFT in 2022, Russia has paid for most of its imports from China in renminbi. This suggests that the PBoC’s swap program may not suffice to challenge the dollar’s systemic role, but in individual cases it enables China to support its allies by using its currency for bilateral trade.

Another way in which the PBoC swaps have been used poses more of a challenge to the global financial order. Since 2012, the PBoC has lent out over US$170 billion to other central banks as a financial bailout to countries facing balance of payments crises or sovereign default. Recipients have used the borrowed renminbi to shore up their foreign exchange reserves or service other debts. For instance, Argentina drew on its PBoC swap between 2014 and 2020 to service foreign debts while undergoing a sovereign debt restructuring. The National Bank of Ukraine tapped the PBoC swap in 2015 to strengthen its foreign exchange reserves during Russia’s first invasion.

The PBoC’s readiness to lend to countries in financial distress distinguishes its swap lines from those of the Fed and the ECB. Indeed, with few exceptions, such as Chile and Hungary, the emerging market recipients of PBoC swaps do not maintain parallel credit arrangements with the Fed or the ECB. China’s use of swaps for financial assistance rather than liquidity provision or trade settlement places the PBoC among other financial institutions that China uses to challenge the international financial safety net built around the International Monetary Fund and create bilateral financial dependencies. The PBoC’s swaps pose a challenge for transatlantic cooperation in financial diplomacy, while its challenge in international payments comes from attempts to re-centre cross-border settlement systems.

The challenge of alternative payment systems

The US’ ability to condition access to essential Western-based financial infrastructures on factors like compliance with sanctions has motivated Chinese efforts to build an alternative financial order. The US can sanction hostile entities directly, but it can also impose “secondary sanctions” on foreign entities aiding sanctioned entities. When the US threatened secondary sanctions against financial institutions aiding sanctioned Russian entities in December 2023 and June 2024, large Chinese banks reportedly pulled out of Russia-related business to avoid being sanctioned. China hopes to be ready with alternatives to maintain trade and investment with other countries if it faces major US sanctions.

To do so, China would need its own messaging system to communicate payments between banks as well as systems for transferring value – clearing and settlement. While SWIFT, the dominant standard global messaging system, is in Europe, it has dropped US sanctioned entities to avoid secondary sanctions.

To achieve its internationalisation and sanctions-proofing goals, China has become more tightly integrated with SWIFT while developing new infrastructures that could reduce reliance on SWIFT. China’s CIPS, launched in 2015, provides a wider scope of services than SWIFT because it goes beyond messaging to move money through clearing/settlement, a full stack that reduces the need for participants to execute payments through dollar infrastructures. But it cannot replicate SWIFT’s core function yet because non-Chinese banks are mostly “indirect” participants in CIPS who still rely on SWIFT to send payment messages for CIPS payments, while direct participants – mostly Chinese banks – can send messages through China’s proprietary system. This pattern illustrates the efficiency of having one global infrastructure, leading Beijing to embrace SWIFT despite the risk of sanctions.

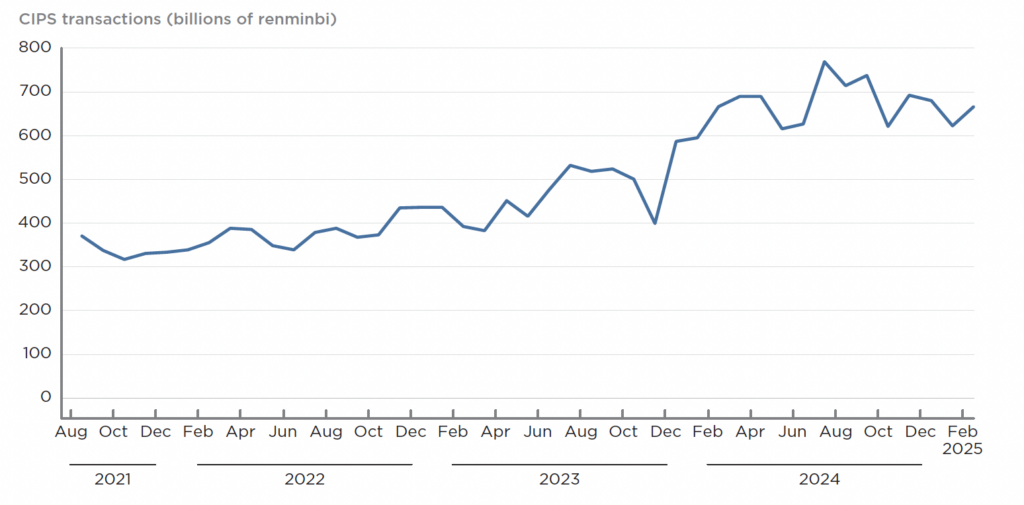

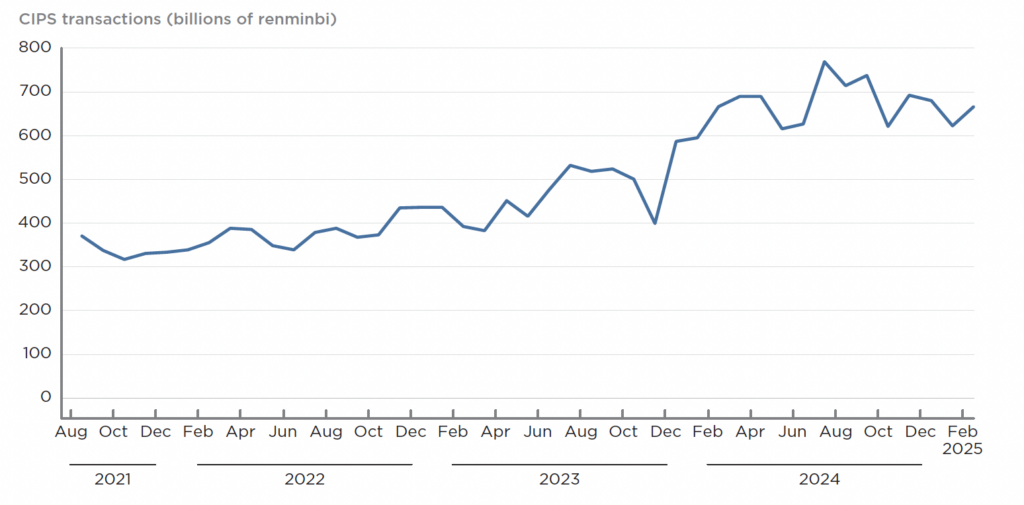

As of March 2024, CIPS had 140 direct participants and 1,371 indirect participants, which would imply that around 90% of CIPS participants are sending messages through SWIFT. Figure 2 shows that CIPS has grown its daily volume of payments by more than 75% since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, from less than 400 billion renminbi to 689 billion renminbi per day over around 31,000 transactions by March 2024. Compared to the 47.6 million transactions communicated through SWIFT daily in 2023, however, CIPS remains peripheral.

Figure 2: Volume of transactions in China’s Cross-border Interbank Payment System, August 2021 to February 2025

Source: Authors’ calculations based on CIPS data. PIIE.

About a third of the increase in use of the renminbi represents Russian attempts to work around the dollar. Yet the remaining two-thirds indicate increasing interest in non-dollar payment channels as insurance against future US sanctions, even among countries not currently threatened with sanctions. Three-quarters of China’s trade is still denominated in currencies other than the renminbi. CIPS and China will be more sanction-proof if more non-Chinese institutions become direct participants and thus do not rely on SWIFT for messaging, though they could still be impacted by secondary sanctions.

Central bank digital currencies

A strategy for working around the dollar further in the future is the worldwide interest in CBDCs, digital forms of central bank money often based on distributed ledger or blockchain technology that may enable new payment infrastructures. If new technology makes payments faster, more efficient and less risky, these systems that could be less reliant on the dollar could gain market share in payments between banks, as privately issued digital “stablecoins” have begun to do for retail payments. Unlike Bitcoin, stablecoins are digital currencies whose value is designed to be stable when measured in terms of traditional currencies. They are usually “backed” by holdings of assets like treasury bonds or cash but can be used for payments on new digital payment systems. They are often used today for international payments, at least for retail users. By contrast, the value of Bitcoin and other digital currencies fluctuate sometimes quite wildly against major currencies like the US dollar, as they are not backed by asset holdings.

All the world’s major central banks, including the Federal Reserve, the ECB, the Bank of England and others are researching CBDCs, and many have pilot programmes exploring whether hypothetical cross-border payment systems based on CBDCs could improve on today’s systems. The PBoC was one of the first central banks to commit to launching a CBDC back in 2016 and has been a leader in exploring cross-border implications.

One of the most promising ideas was M-CBDC Bridge, started under the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) with the central banks of China, Hong Kong, Thailand and United Arab Emirates. A pilot programme directly transacts CBDC among central banks and commercial banks with no role for the US dollar or SWIFT, albeit in small volumes. While the project aims to build a functional payment architecture, major hurdles from governance and risk management to foreign exchange conversion would need to be surmounted. The project has also proven politically controversial.

Soon after, the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) stepped up rhetoric about jointly building a new BRICS cross-border payment system, which Russia deemed the “BRICS Bridge”. These efforts became a bridge too far for the BIS, which pulled out as it could not risk being seen as contributing to efforts to bust sanctions. As a result, M-Bridge’s future is in doubt.

The Federal Reserve and the Eurosystem’s central banks are working together on other BIS projects like Agora – which does not include China – that include cross-border payments, but they diverge in their enthusiasm for use of CBDC at home. The ECB is developing a CBDC for retail use in the Eurozone in part to enhance its financial independence from the United States, while the Federal Reserve been more conservative.

CBDC systems do not represent a near-term threat to dollar dominance because they remain in their infancy. No major economy has a fully operational CBDC. Thus, even if China becomes the first, it will not have any network of CBDCs that would give it an advantage in supplanting the dollar. The EU and US should, however, continue to carefully monitor CBDC developments for breakthroughs to ensure their currencies and financial institutions can engage with new infrastructures that gain traction.

Conclusions

Chinese efforts to establish parallel financial infrastructures and promote the renminbi as an international settlement currency need to be taken seriously, especially with the greatest headwinds to US dollar dominance in many years, even if they pose no short-term risk to the dollar or euro’s roles. As Russia’s shift to Chinese financing since 2022 suggests, both central bank swaps and the CIPS system can function as safety valves for countries cut-off from Western financial systems, even if secondary sanctions retain their power to force major Chinese entities to cut off trade with sanctioned entities.

China’s limited success in actively stimulating wider international usage of the renminbi speaks to the inertia of the global financial system and the reluctance of Chinese policymakers to further relinquish control of their capital account, but neither can be taken for granted in perpetuity. The renminbi may be valuable as a settlement currency for bilateral trade with China, and thereby impact many countries, but it is more difficult to overcome the established roles of the dollar and euro for trade between third parties.

Nonetheless, as alternative systems like CIPS become more established, the risk will rise that sanctions overreach will push countries into Chinese settlement systems and renminbi usage. Moreover, China’s use of swap lines may undermine the multilateral financial safety net and require more attractive and accessible financial assistance facilities in dollars and euros to maintain global financial stability. The Fed and the ECB’s recent standing repo facilities are positive steps in that direction, which could be extended to more countries. Beyond judicious use of sanctions, US and European policymakers should avoid complacency and continue to improve the incumbent systems to leave less space for China to present a more attractive alternative.

__________

The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for Security, Diplomacy and Strategy (CSDS) or the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). This Policy Brief is a revised version of the paper presented at the conference on Transatlantic Perspectives on US-China Geoeconomic Competition in Washington, DC, on 29 January 2025, jointly organised by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) and the Centre for Security, Diplomacy, and Strategy (CSDS) at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel. A version of the paper can be found at PIIE. The authors gratefully acknowledge insightful comments from Dong He (IMF), Federico Steinberg (Georgetown University), and participants at the PIIE-CSDS conference. This Policy Brief is partly funded by the European Union through a European Research Council grant on Sino-American Competition and European Strategic Autonomy (SINATRA) under grant number 101045227.

ISSN (online): 2983-466X