CSDS POLICY BRIEF • 33/2025

By Beatrice Heuser

17.12.2025

Key issues

- Russian military thought increasingly seeks to blur the line between peace and war;

- And yet Russian narratives deny waging “war” against Georgia in 2008, Ukraine since 2014 (or even 2022) or ever attacking any other country, portraying aggression as purely defensive;

- Similarly to “Realism”, Russian strategic culture treats war as a permanent condition, challenging the West’s notion of armed force being limited by international law.

Introduction

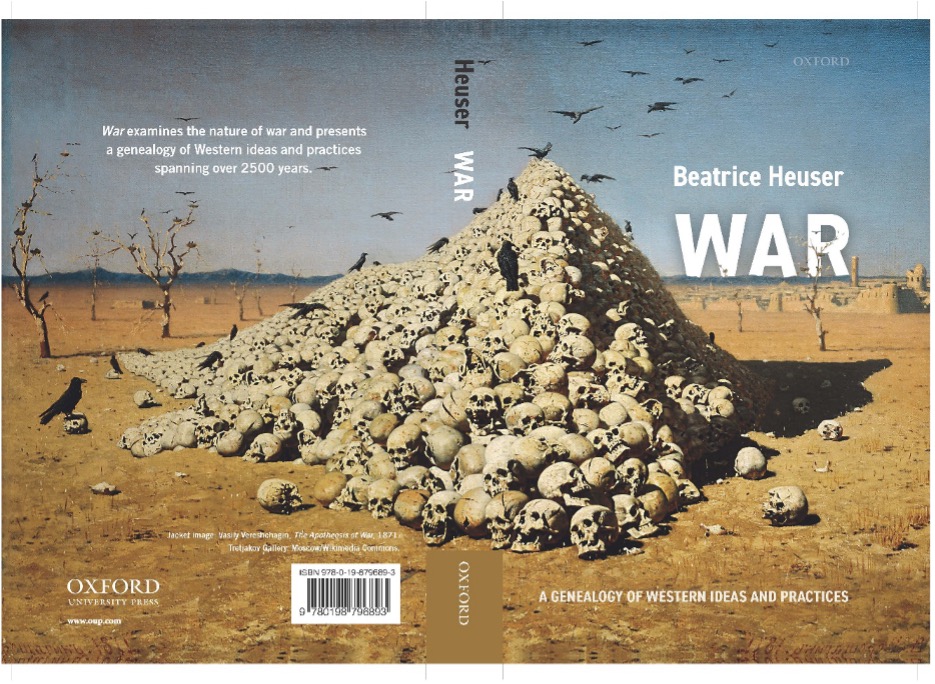

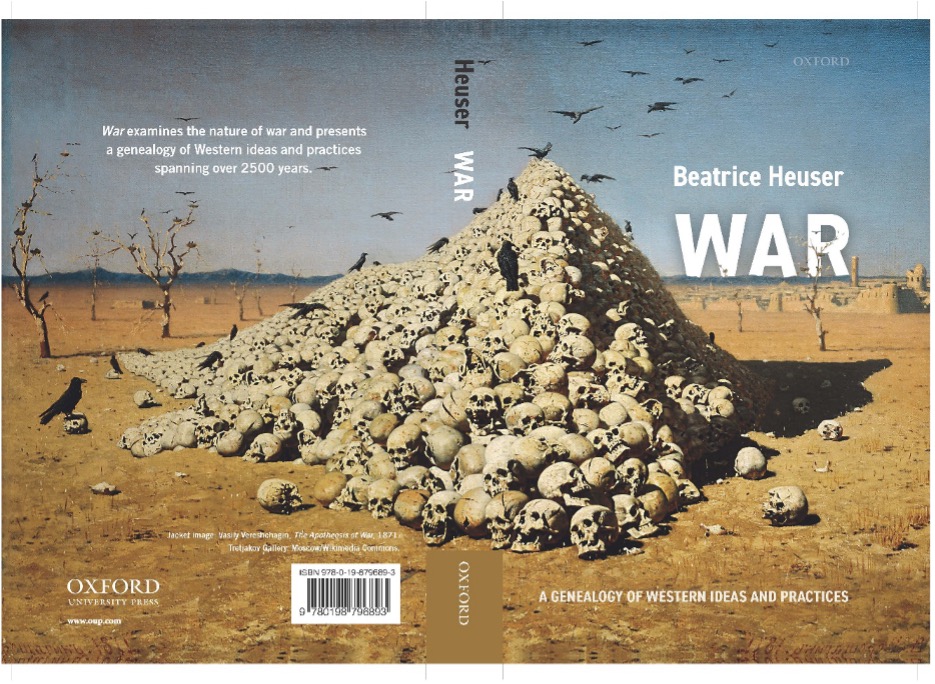

In March 2022, within a few days of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s all-out invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces, this author published a book that traced the evolution or genealogy of “Western” ideas about war (Heuser, 2022). Its cover shows a Russian painting by Vassily Vereshchagin, who initially called it “the Triumph of Tamerlane”, but later renamed it “The Apotheosis of War” (see the image below). He dedicated it to “All conquerors, past, present, future”. Painted in 1871, Russian gallery owners who exhibited his other work recoiled from showing it as it seemed at odds with government views and the prevailing Zeitgeist. When it was exhibited in Berlin in 1882, Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke (the Elder), the head of Prussia’s armed forces, forbade Prussian soldiers to go and see it, and the Austrian War Minister is said to have done the same for his forces (Art Challenge, 2025). Criticism of war and of bellicose policies was not welcome on the European continent at the time.

Not counting the Yugoslav Wars of Secession of the 1990s, Putin’s war on Ukraine is the first inter-state war in Europe since 1945. Russian thinking about war thus deserves further examination. It is at odds with the 20th-century development, led by Europeans and Americans (whom I shall, as a shorthand, subsume under the term “West”), of an international order based on the cardinal rule that Thou Shalt Not Attack Other States.

The two pillars of Western ideas about war

The Western tradition of thinking about war, evolving over twenty-five centuries, gravitated towards consensus on two key points. These are, first, that war can be justified only in terms of defence or the righting of a previously received wrong, which is the essence of a European-Western Just War Tradition. The one exception to this European tradition is found in the 19th century, when the right to go to war regardless of any justification was recognised as the right of any sovereign state (Heuser, 2022: 67-126). This view of war as an innate tool of sovereign state power was abandoned in 1928 with the Briand-Kellogg Pact outlawing war, at the initiative of the French and American foreign ministers of those names. After being signed and ratified by over 50 states, including the Soviet Union, it is still in force and eventually became the foundational creed of the United Nations (UN) as enshrined in its Charter. It rules out fighting except in self-defence or in defence of an attacked state, or of UN-authorised intervention in case a government puts its mind to massacring its own population. It is the central rule of the international order for which the UN stands, and which until November 2024 was generally supported throughout the “West”, notwithstanding some breaches of this rule by the United States, Britain and France.

“The Apotheosis of War”, by Vasily Vereshchagin

Secondly, there is consensus that war – if the term is not used metaphorically – includes physical, kinetic force, violence, acts of destruction, maiming and killing, or, as summed up famously by Carl von Clausewitz in 1832: ‘war is […] an act of force to coerce the adversary to fulfil our will […] Force, i.e. physical force […] is thus the means; to impose our will on the enemy, the purpose’ (On War, Book I, Chapter 1).

Are both of these central pillars of Western thinking about war also shared by Russia?

Turning, first, to the Just War tradition, there seems to be some recognition in Russia today that initiating war is problematic. Significantly, even after February 2022, the Russian government calls its actions in Ukraine not a war, but a “special military operation”. The Russian press was banned from using the term “war”, even if with the occasional slip of the tongue, Putin used this word (IIyushina, 2022). Paradoxically, this meant playing down this act of force while simultaneously arguing for the upgrading of non-violent actions ascribed to ‘the West’, ‘the USA and its NATO Allies’ or ‘the Anglo-Saxons’ (Kostenko in Heuser, 2025: 103) to constitute ‘war’, as we shall see.

Concomitantly, Russian leaders have been going to impressive contortions to present Russian aggression – first, against Georgia in 2008, and since 2014 against Ukraine – as defensive and thus just. Russian government spokespeople, journalists of state-controlled media and military authors have claimed all along since 2014 that ‘[t]he so-called ‘Ukraine Crisis’ [was] provoked by Western politicians and the Russian Federation’s forced response’ (Mazhuga and Tolstykh in Heuser, 2025: 103) amounted to self-defence against Western provocation or even “aggression”. The enlargement of NATO to include countries from the former Russian sphere of influence or even former parts of the USSR is described as aggression, as is the West’s support for Ukrainian independence, purportedly defended only by “Nazis”. Putin himself, in November 2024, told an international audience in Sochi that: ‘our country has never been the one to initiate the use of force: we are forced to do that only when it becomes clear that our opponent is acting aggressively and is not willing to listen to any type of argument’ (Putin, 2024).

Some Russian commentators see an ongoing clash of civilisations (even if Samuel Huntington is not explicitly cited in this context) between the “Russian civilisation” and a Western drive for globalisation. The West is seen as trying to destroy native cultures while forcing supposedly purely Western values upon the rest of the world, with a ‘matrix of governance, consumerism, and socio-economic hierarchy, leveraging a wide [range] of achievements in economics, science and technology’, in the words one influential author, the weapons engineer Aleksandr Georgievich Semenov (Semenov in Thomas, 2019). Upon closer inspection, those Western values were, particularly, ‘rampant radical feminism (the “Me Too” movement), Black racism (B[lack] L[ives] M[atter]), aggressive gender and green agendas’ (Brovko and Chikharev, 2023: 29).

This is quite a shift away from the lip service which the USSR paid to the equality of Soviet citizens of all ethnic origins, and to gender equality, and which it practised insofar at least that it strongly encouraged women to join the work force, provided childcare, and made efforts to create a general homo sovieticus. The supposedly subversive Western values regarding gender equality and all the other human rights were ostensibly also the Soviet Union’s when it contributed to formulating, and then signed up to, the legally binding International Conventions of 1966 on Civil and Political and Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see Article 26 in the Convention). The Russian Federation, as heir to the Soviet Union, is bound by these treaties. Yet its spokespersons seem unfamiliar with their contents. Some cultures are more scrupulous about upholding rules and definitions. Others dismiss treaties as mere scraps of paper when it suits them, incidentally a view that was widespread throughout Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It seems that today’s thinking among the Russian leadership has returned to that of the era of great wars.

The “Western” threat to Russia and other countries is also described in terms of the undermining of their spiritual and moral foundations, and what General A.V. Serzhantov, doctor of military sciences, Deputy Commander at the Military Academy of the Russian General Staff and also Deputy Director for Research, has called “Consciential War” (Serzhantov, 2021: 62), aiming at changing their values and sowing in their consciousness critical attitudes towards their own societies, elites and government (Thomas, 2019: 107). The “othering” of “the West” is thus important for the Russian self-perception and for the apportioning of responsibility for the revival of a threat to Russia from the West against which Russia has to defend itself. Russian self-perceptions and perceptions of what constitutes “the West” need to be examined further before returning to that other key view of war.

Is Russia part of “the West”?

There has been a long-standing debate amongst Russians, going back at least to Peter the Great with his modernisation drive under the influence of cultural developments in Central and Western Europe, as to whether Russia belongs to the West or the East, is European or was sui generis, neither Asian nor European. Some saw Russia as the leader of a Slav world distinct from Germano-Latin Europe, others again claimed that Russian thinking mixes Eastern and Western ideas (Fridman, 2022). Russia is, of course, a scion of Europe, and its heritage in terms of ideas is squarely European, just as German ideas, even in Germany’s catastrophic deviation under National Socialism, were ultimately derived from perverted ideas rooted in the Euro-Mediterranean civilisations.

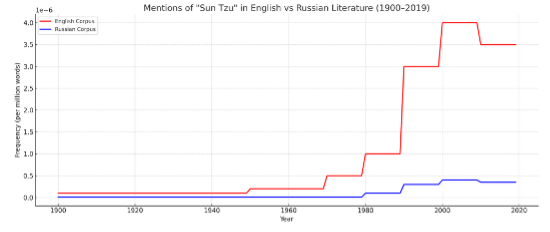

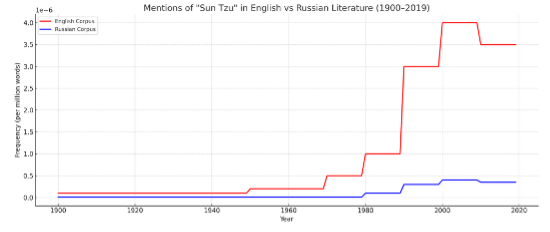

There is a tradition critical of Russia, arguing that it is strongly imprinted in its collective mentality by centuries of Mongol occupation and repression. The tendency to impose and accept repression, the lack of a civil society and self-organisation to criticise openly and stand up against authoritarian governments may well reflect this. A more extreme argument, however, that Russian ideas are in themselves Asian, simply cannot be upheld, as one cannot find references in Russian philosophy or political theory or military literature to Eastern thinkers – with one exception, that of Sun Tzu. After a brief period of interest in the late 1940s as the Chinese Communists were gaining ground and then winning in the Chinese Civil War, renewed Russian interest in Sun Tzu came as an import from America, where the rediscovery of Sun Tzu during and after the Vietnam War promised to open a window to the “Asian Mind”, which had clearly outfoxed the Western minds in the South-East Asian conflict (See Figure 1). Russian ideas on war, like those of all the other European powers, thus form a kaleidoscopic pattern of concepts drawn from the Judaeo-Graeco-Roman heritage, filtered through the East Roman-Byzantine and Greek Orthodox heritage.

Figure 1: Sun Tzu in English and Russian Literature (1900-2019)

Note: This graph, produced with the help of ChatGPT, used Google Ngram to compare the Russian and English literature corpus to show the frequency of mentions of “Sun Tzu” in English and Russian literature from 1900 to 2019. The English corpus shows significantly higher and earlier growth in mentions, especially from the 1970s onward, while the Russian corpus starts much later and remains at a lower frequency throughout.

Ever since Soviet Communist Party ideologue Andrey Zhdanov at the founding meeting of the Communist Information Bureau in the autumn of 1947 proclaimed the world to be divided into imperialist and anti-imperialist camps, the former led by “Anglo-Franco-American imperialists” (Zhdanov, 1947), synonyms used for the former in the Russian discourse included “Western”. Increasingly, as Stalin’s respect for the United States grew and that for the United Kingdom diminished, the “USA” or “America” became the main target of Soviet verbal attacks. From the 1950s, “NATO” was accused of planning aggression against the Soviet-led Communist sphere. This enemy image persisted in Russian military literature in the 1990s, even as Western governments reached out to the governments of Gorbachev, Yeltsin, and, from 1999, also Putin, who for some eight years seemed willing to play a constructive part in international relations and to build up the strength of his country by peaceful means. Obviously, with the demise of Communism in Russia, the term “imperialist” initially fell out of usage. But NATO and the United States continued to be the target of Russian criticism, with special and unceasing reference to NATO’s intervention in the Serb military operations against Kosovo in 1999, and to “NATO’s expansion” to bring in former member states of the Warsaw Pact and even of the defunct USSR in the form of the Baltic States. When Russian anti-Western polemics picked up again after Putin’s Munich Security Council speech in 2007, NATO continued to stand in the forefront of all Russian descriptions of a threat, while the European Union was rarely, if ever, referred to.

Today’s Russia, just as the USSR in the past, shares with East and South-East Asian societies, especially Communist societies, the emphasis on the interests and well-being of society as a whole (for which large numbers of humans might have to be sacrificed) rather than on the liberties of the individuals (Fridman, 2022). This is, of course, both a feature of the much older Asian cultures and of Marxism-Leninism.

Yet the Russian narrative of Russia’s history has in common with most other European nations a self-perception of being the antemurale Christianitatis, defenders of Christendom against barbaric forces without, be they Mongol or Ottoman Muslims (enemies shared by most East European countries, or, in the case of West European nations, the enemies were also Arab Muslims or pagans). Nor are they singular among Europeans in seeing themselves as defenders of the proper faith against heretical deviations, a self-image shared by all European societies. Only, that in Western Europe, secularism has gained ground to the point where faith issues are more common among immigrants than among the receiving nominally Christian populations.

Nor is Russia alone in having a narrative of national exclusivity, specialness, originality, incomparability and seeing itself as having a messianic mission, what Dmitry Biriukov calls a “widespread psychic contagion” that affected Europe especially in the 19th and early 20th century (Biriukov, 2025). The German Sonderweg is a variation on this subject; the French as new Israelites and France’s special mission civilisatrice is another one; Poland as the “Christ of nations” sacrificed for Europe yet another (Wohlfeld, 1995: 90f); Britain with its supposed particularity that led to Brexit (Varsori in Buffet and Heuser, 1998); Sweden’s special calling to be a moral superpower (Dahl in Buffet and Heuser, 1998); and so on: it seems all European identity narratives wanted to cast their nations as special, and the religiously-minded engaged in a “my nation is holier than thine” competition (Heuser and Buffet in Schöttler, Veit and Werner, 1999).

The defence of the cultural mix of Russian Orthodoxy, Russian “spirituality”, backwards-looking nationalism that finds its source of pride in Russia’s imperial past, and “traditional family values” is now being touted as Russia’s holy task in the face of supposed subversive “Western” values. It is not without poignancy that we now find “traditional families” and values promoted by the National Security Strategy of the Second Trump Administration, along with ultra-nationalist parties in Europe and the plan to abstain from encouraging other than already ‘like-minded friends to uphold our shared norms’, (if they are like-minded, why do they need pushing?) ‘without imposing on them democratic or other social change that differs widely from their traditions and histories’ (US Government, 2025). But then, unlike the USSR, the United States never ratified either of the 1966 Covenants on human rights.

Given that a Russian government spokesperson, Dmitry Peskov, has pronounced the published 2025 US National Security Strategy as ‘largely consistent with our vision’ (Muller-Heyndyk, 2025), it will be interesting to see whether the term “West” and the United States, as a designated adversary, will now disappear from Russia’s strategy literature and foreign policy discourses. Presumably, it will be replaced by “the EU” or “Europe”, but the latter, again, begs the question of what Russia is, if not a child of Europe.

What is war in Russian thinking?

Turning then to views of war, one might start with the neutral ground that after 1945 was agreed upon by both the USSR and the West, International Law, which is mainly concerned with defining when a “state of war” or armed conflict sets in, rather than what it consists of. For the latter, we only have the International Law Association’s (ILA) advice to go by, which defines “armed conflict” only in terms of minimum criteria to be fulfilled, namely ‘the existence of organized armed groups’, and that these are ‘engaged in fighting of some intensity’, where the scale of either the groups (e.g. number of participants) or the intensity of the fighting (e.g. number of casualties) is left undefined (Heuser, 2022: 110ff). In the Geneva Conventions of 1949, the term “armed conflict” has been widely accepted to encompass violent struggle where at least one party is not a state (Heuser, 2022: 110ff). The scale of this is deliberately not defined.

The Russian Greater Law Dictionary of 2003 defines “armed conflict” as: ‘incidents involving the use of arms, armed actions and other armed clashes of limited scale, which can be the result of attempts to resolve national, ethnic, religious and other conflicts by means of armed struggle’ (Malyshev, Pivovarov and Khakhalev, 2022: 31). That seems to diverge from the International Law Association criteria only in that it points to a “limited scale” where the former does not comment on the scale. According to a somewhat amateur trio of Russian military officers, who purport not to know how the use of “armed conflict” came up and instead attribute it to NATO parlance in the 1950s (Malyshev, Pivovarov and Khakhalev, 2022: 27), the difference between “war” and “armed conflict” go further: the former, they think, must end in the defeat for one party, while ‘in an armed conflict, victory is not mandatory, hostilities can be ended in various forms and ways’ (Malyshev, Pivovarov and Khakhalev, 2022: 34). How far this opinion is shared by the Russian government’s definitions is unclear, but it would have implications for a settlement of the Russo-Ukrainian War (especially as elsewhere, along with other errors, they claim that war and armed conflict can only exist where one side is a state, (Malyshev, Pivovarov and Khakhalev, 2022: 29), which is not a stipulation of the Law of Armed Conflict).

A more informed approach to defining war can be found in an article dating from 2021, written by the prolific General Serzhantov. Classically, it builds on Sun Tsu, Machiavelli, Clausewitz, the Russian military theorists Andrei Evgenyevich Snesarev and Aleksandr Andreyevich Svechin (both eventually discredited by Stalin) and the Russian exiles General Nikolai Nikolayevich Golovin and Yevgeny Edvardovich Messner. Staying true to the writings of these and to the Russian Military Encyclopedia, where war is defined as ‘a sociopolitical phenomenon, a special condition of society related to a radical change in relations between states, peoples, social groups, and to the transition to organized use of armed violence assets to attain political goals’. Serzhantov summarised this as meaning ‘a form of settling differences by means of military violence’ (Serzhantov, 2021: 57 and 61).

Can one be at war when force is not used?

While the Russian government did not want to see its undercover operations in Ukraine since 2014 or even its 2022 invasion of Ukraine as “war”, it has for some years now homed in on “hybrid war”, a Western expression first coined by US strategist Frank Hoffman to describe hostile Russian operations against other countries that fell and fall under the threshold of the use of force. Fascinated as well as outraged by NATO’s success in staving off a Serb military occupation of Kosovo in 1999 through an air campaign, by NATO’s air campaign against Libya in 2011 and by Russian air strikes on warring parties in Syria, Russian military leaders authors developed a theory about how future war would be fought from a distance, as “no contact war”. They also developed the theory that the US and NATO powers were fighting Russia by non-military means, which they in turn attributed to Western actions only (Fridman, 2018).

A debate then ensued among Russian military authors as to whether violence, the use of armed force, was required for something to be called war, particularly if directed against Russia. The starting point of this debate was always Clausewitz’s aforecited definition that war is ‘an act of force […] physical force’ (On War, Book I, Chapter 1). This limitation has been debated in Russia ever since (Fridman, 2022). There are two schools today: on the one hand, the traditionalists, such as Colonel Sergey Chekinov and General (ret.) Sergey Bogdanov, both of the Centre for Military and Strategic Studies of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces, who argued in 2013 that: ‘the criterion for the presence or absence of war is the place and role of military and non-military means in a political confrontation […] a political confrontation in which […] the troops only have an impact because of their mere presence or an action without the use of fire and strikes […] it is not war’ (Fridman, 2018: 129).

Even in 2017, they still insisted that ‘armed struggle remains a crucial factor’ in defining war (Chekinov and Bogdanov in Thomas, 2019: fn 81; Fridman, 2018). Or, as Brigadier (ret.) Borchev put it in 1993, war is: ‘the use of all or some of the forms of force (насилие) and of strife for the resolution of contradictions, and the realisation of the ultimate political objectives depends on the capacity of the State’s (or coalition of States’) political leaders to use them in an appropriate and flexible way’ (Minic, 2023: 139).

The traditionalists included the military authors Colonel Babich and N.M. Vasil’ev, O.M. Gorshechnikov, A.I.Malyshev, Yu.F. Pivovarov, and importantly, initially, General Makhmut Gareev, the doyen among Russian strategists of the post-Soviet era (d.2019). In 2007, Gareev stated that ‘the over-free employment of such a word as “war” devalues the severe [nature of this] concept and dulls its adequate perception in society’. And in 2017, he wrote that ‘if an employment of any non-military means is war, then the whole of human history is war’ (Fridman, 2018: 158).

The revisionist school, however, held that Clausewitz’s limitation of war to the use of physical (i.e. armed) force (насилие) is outdated. They included Brigadiers Danilenkov and Borchev, Admiral V.P. Gulin, Colonels Dremkov, Andreev and Shalamberidze, and General A.I. Nikolaev, who wrote in 2003, of course, starting with Clausewitz:

‘Let’s take a well-known definition of war as the continuation of politics by other means – means of force (насилие). What is particular about these means is that, well before they are applied, they are already an extension of politics by the force of their moral, psychological and techno-scientific pressure on neighbours. Intelligence gathering and counter-espionage, corruption and blackmail, psychological pressure, […] disinformation, discrimination in the international sphere, and finally, demonstrations of armed force can continue and will continue until the declaration of war, but this is not peace […] If you look at the world situation […] war has never ceased’ (Minic, 2023: 147).

Then, in 2017, shortly after dismissing the application of the term “war” to non-military means as we have seen above, Makhmut Gareev shifted his weighty authoritative support to the other side in the debate. Writing together with a colleague, he now argued that:

‘it is […] urgent to introduce an amendment to the defence legislation of the Russian Federation so as to enable Russia to take measures to push back pertinent threats and, if necessary, to declare a state of war, not only in case of an armed attack […] but also […] [of] a threat to national security in the areas of the economy, ideology, information […] a military doctrine and an appropriate structure of the State’s military apparatus should be developed’ (Minic, 2023: 178).

General Serzhantov put an interim end to this debate when he decreed, in 2021, that the traditionalists were right to hold that armed struggle had to be part of war or armed conflict, but that there were three ways in which wars now differed from previous times: with new actors (“civilisational associations”, “non-existent States” – he seemed to think of the self-proclaimed “Islamic State”) joining old actors (states), and classical conflicts which earlier, drawing on Machiavelli, he had defined as self-enrichment and the weakening of the enemy, being replaced by ‘conflicts between cultures’. The latter he defined as the use of military force to impose on a victim country ‘the civilizational values of the dominant state’. As an example of this, he cited Western Europe trying to impose its values and democratic standards on Iraq and Libya (Serzhantov, 2021: 61f).

The second difference noted by Serzhantov concerned the use of new technologies, allowing ‘contactless confrontation involving precision-guided weapons’ (i.e. armed conflict without direct contact between combatants (Serzhantov, 2021)), and the third, supposedly “new”, non-violent kinds of confrontation in the ‘economic, informational, political, etc.’ spheres. With this, he doffed his hat to the reformers, and presumably this means that some part of the enlarged syllabus called for by Brigadier Vladimirov eight years earlier is by now approved. It was in this context that he coined the term “Consciential War” (Serzhantov, 2021: 62).

War: good, bad or simply inevitable

General Nikolayev’s view that if you look at world history, ‘war has never ceased’, of course, echoes Plato’s notion that ‘all are involved ceaselessly in a lifelong war against all’ (see The Laws, 1.625-626). It has a long history also in the “West”. It became somewhat less fashionable in Europe since the Fascists and National Socialists embraced it so eagerly in the 1930s and 1940s, although the Western “Realist” school of International Relations Theory – widely read and cited in Russian military literature, passed review here – takes a similar view.

In the run-up to the First World War, Russia had its share of militarists, just like most other Continental European countries (Biriukov, 2025). Russian generals from the 19th century Genrikh Leer to Aleksandr Vladimirov, in our own time, argued that war is an inherent and eternal part of human nature and existence (Leer, 2021; Fridman, 2022). They might have been mistaken for Prussians – their arguments matched those of Moltke the Elder, Rudolf Caemmerer, Friedrich von Bernhardi – or even French – think of the Jeune Ecole of naval strategists (Heuser, expected 2027). For such views went hand in hand with the Social Darwinism so popular at the time (Heuser, 2012). Equally, when other Russians like General Martynov in 1899 expressed his hope that one day ‘diplomacy will find a way to abolish armed clashes between people’, he – and Russian jurists who played a leading role in the huge advances in International Law at that very time – could have been writing as an American or a Swiss or any Westerner with this more humane Whiggish mentality (Ivanovich Martynov, 2021).

Russia historically stood and today stands fully in the Byzantine ideational tradition of seeing war as part of the human condition, of the eternal sinfulness of man, that cannot be eliminated permanently by human endeavour (Chrysostomides, 2001; Chatzelis, 2025). In the 19th century, a few Russian intellectuals developed their own brand of Christian pacifism independent of that of Western sects such as the Quakers or Amish. Among them were Tolstoy and Zinaida Gippius, a playwright, poet and religious thinker who, even on 5 November 1914, held an impassioned public speech against the war. And we have already mentioned Vereshchagin, who, having travelled through Russian-ruled Central Asia in the 1860s and horrified by remains of previous massacres, with his “Apotheosis of War” took a clearly anti-war stance.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky articulated ideas from both the militarist and the pacifist camp in his Paradoxalist (Morson, 1999), and his friend, the philosopher Vladimir Solovyov (1853-1900), who, initially sympathetic to Tolstoy’s pacifism, later began to see more sides to the argument. Both Dostoyevsky and Solovyov cast their discourse on war in the form of the conversations (Biriukov, 2025). In Solovyov’s War and Christianity, first published in 1900, a key figure, a very educated general whose talk is replete with references to the European classics, shares his distress that war, previously considered to be “something holy”, and his profession – over centuries one held in highest esteem, with all male Russian saints being either monks or soldiers – are suddenly cast into doubt. The politician responds:

‘Even formerly, everyone always knew that war was evil and the less of it the better, and, on the other hand, wise people know now that it is a kind of evil which cannot yet be removed once and for all in our time. The problem is not the complete abolition of war, but its gradual limitation and isolation within certain narrow boundaries. The fundamental notion about war remains what it has always been, i.e., that it is an inevitable evil, a calamity which must be endured upon extreme occasions’ (Solovyov, 1915: 5-7).

Yet, as the general opines, war can be virtuous; if fought virtuously, it can even be “something holy”.

The politician claims that his own ‘point of view is the ordinary European one, which, by the way, nowadays, even in other parts of the world, educated people are beginning to assimilate’ (Solovyov, 1915: 12). Indeed, the fact that these works were translated into Western languages, and of course, particularly in the case of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, became a classic of European literature, speaks for the Europeanness of their ideas.

The Russian Revolution ushered in seven decades of Marxist-Leninist teaching about the inevitability of war until the world had become a Communist paradise. The Great Fatherland War (the Second World War), with its 26 million or so Soviet dead, was interpreted as a great triumph, with Russia, Christ-like, having gone through passion to resurrection. Grieving was discouraged, but the scars left on the Russian psyche by this enormous suffering are still affecting Russian attitudes to war today. This is perhaps true even more so now that the war is once again central to the Russian identity narrative, with military parades on 9 May (the date of the end of the Second World War in Russia) since 1995 replacing the customary October Revolution commemoration parades (Michlin-Shapir, 2021).

That the word “enemy” has become conterminous with “Nazism” in Russian thinking is also understandable, and amply explains the curious transposition of “Nazism” onto the Ukrainians who refused to come back under Russian imperial domination in the early 21st century. The Russian official narrative constructs a continuity between the Ukrainian movement of independence from the USSR in the Second World War that sought to pursue secession with the help of the German occupation forces, only to find that the National-Socialist ideology put Slav Ukrainians firmly in the category of Untermenschen, lesser humans, and was thus no better than the Russian-dominated Soviet regime. The principal aim of the Russian aggression has thus been defined as “de-Nazifying” Ukraine and restoring its populations’ consciousness of belonging to the Russian cultural sphere (President of Russia, 2022). (This “Consciential War” for one has been singularly unsuccessful.)

Stemming from the Byzantine view of man’s sinfulness, there is a greater acceptance in Russia than in the rest of Europe of the “Realist” idea that war continues to be and will forever be part of the human condition. In contrast to Greek Orthodoxy, however, Russian Orthodoxy under the guidance of Metropolitan Kirill of Moscow has recently developed a strongly martial spirit that has flourished in the convergence of interests between Putin and the Russian Church (Adamsky, 2019). Kirill sanctified the use of force by Russia to the point of promising Russian soldiers killed fighting against Ukraine the remission of their sins (Radio Liberty, 2022), something last encountered in the West during the crusades, but never accepted by the Greek Orthodox Church.

Conclusion

In conclusion, given that Russian leaders believe that war is an inevitable part of human existence, Gareev’s and Turko’s call for the revision of Russian legal definitions of war is of consequence. It is what allows the Russian government to argue vis-à-vis their own publics and an undiscerning international audience that the military invasion of Ukraine is a legitimate act of self-defence against non-military ‘unfriendly acts of foreign countries’. While Westerners argue that it is desirable to keep up not only the Law of Armed Conflict but also the distinction between a state of war and a state of peace (Heuser, 2022), the lip service paid by Putin to this distinction is mendacious, as the fate of Ukraine, with its hundreds of thousands of military and civilian casualties, demonstrates. Contrary to what the Russian government argues, it is not the West that is ‘weakening […] universally recognised norms and principles of international law’ (Russian National Security Strategy, 2021) pertaining to the use of armed force, but it is Russia that thus opens the gates to the re-legitimising of the use of armed force in furtherance of States’ subjectively defined interests, contrary to the international order based on the UN Charter. If this is more generally accepted, then our perhaps most important civilisational acquis with regard to war will have been toppled. It is for this reason that, as Yugoslav military ethics Professor Jovan Babić has put it, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has been a “game-changing event”, not just for Yugoslavia and Russia, but for the world (Babić, 2022).

The author would like to thank Dr Ofer Fridman for all he has taught her.

__________

This CSDS Policy Brief is a deliverable of the Future of European Deterrence (FED) project. The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for Security, Diplomacy and Strategy (CSDS) or the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). Image credit: Kirill Beglaryan, 2022. Image credit: 1871 Vereshchagin Apotheose des Krieges anagoria.

ISSN (online): 2983-466X