CSDS POLICY BRIEF • 23/2025

By Salih Isik Bora and Shea Rueda

2.9.2025

Key issues

- High-profile cases like the United States’ (US) export control actions against Dutch firm ASML have spurred European Union (EU) calls for a unified export policy, as highlighted in the 2024 Commission White Paper on Export Controls;

- While the EU has been attempting to make strides in this field since Regulation 428/2009 on dual-use exports, existing legislation only consists of coordination mechanisms;

- If the EU is to elaborate a coherent Economic Security Strategy, export controls are a key component. However, resistance from larger member states remains a major obstacle.

Introduction

On 17 October 2023, the US Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) decided to significantly expand its export control rules on lithography equipment – machines able to carve vanishingly small patterns onto silicon wafers – as part of its broader attempt to restrict the People’s Republic of China (PRC) access to the most cutting-edge semiconductors. While the previous framework subjected certain PRC-based entities’ purchases of lithography equipment below 1.5 nanometres(nm) Dedicated Chuck Overlay (DCO) accuracy to a presumption of denial, this threshold was increased to 2.4 nm under the expanded rules. This has meant that the US has retroactively expanded its export control rules to include two older generations of lithography equipment: the NXT:1970i series, released in 2013, and the NXT:1980i series, released in 2015.

The catch here is that neither NXT:1970i nor NXT:1980i machines are manufactured on US soil or by US-based corporations. They are both made by the Netherlands-based company Advanced Semiconductor Materials Lithography (ASML). Furthermore, there were not sufficient “American” components or know-how in ASML machines to meet the 25% de minimis requirement for imposing export controls on a foreign product. The BIS thus lowered this threshold to 0%, effectively instating complete extraterritoriality in the implementation of export control rules.

This unilateral decision was met with considerable uproar in both ASML and the Dutch Parliament. The new BIS rules were especially perplexing for many stakeholders in the Netherlands because The Hague had cooperated with US authorities and restricted the sale of ASML’s most sophisticated equipment to China, first the Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) equipment in 2019, and then many of the less advanced Deep Ultraviolet (DUV) equipment in the first half of 2023. The Netherlands had autonomously updated its export control framework as recently as June 2023 to comply with US rules. This was, however, “too little, too late”. US authorities were concerned that The Hague’s resolve in addressing Chinese military modernisation was diluted by commercial considerations. Meanwhile, ASML exports to China continued to increase at a steady pace despite export controls. In 2023, they made up as much as 25% of the firm’s total sales, the highest level they have attained so far. As a result, the US chose to override the Netherlands and pace ahead in expanding export controls.

It was against the backdrop of this event that the European Commission released the “White Paper on Export Controls” in January 2024, which articulated various reforms that could be made to synchronise European export control policies and take steps towards creating a common export control regime. In a thinly veiled reference to US-China tensions, the European Commission justified the need for a common export control policy on the basis that ‘the lack of a common EU voice exposes individual Member States to geopolitical pressures’. Accordingly, ‘allies or like-minded partners may seek alignment with controls designed based on their own security assessments and interests, while third countries likely to be subject to controls may threaten individual Member States with retaliation’.

These developments warrant an evaluation of the previous implementations of export control policies and an analysis of new proposals being made by EU institutions. This CSDS Policy Brief will describe the recent history of export controls and then discuss the White Paper’s recommendations by assessing its feasibility, potential roadblocks and how EU institutions have signalled their intent to implement reforms to the current regime of export controls.

A history of export control policies

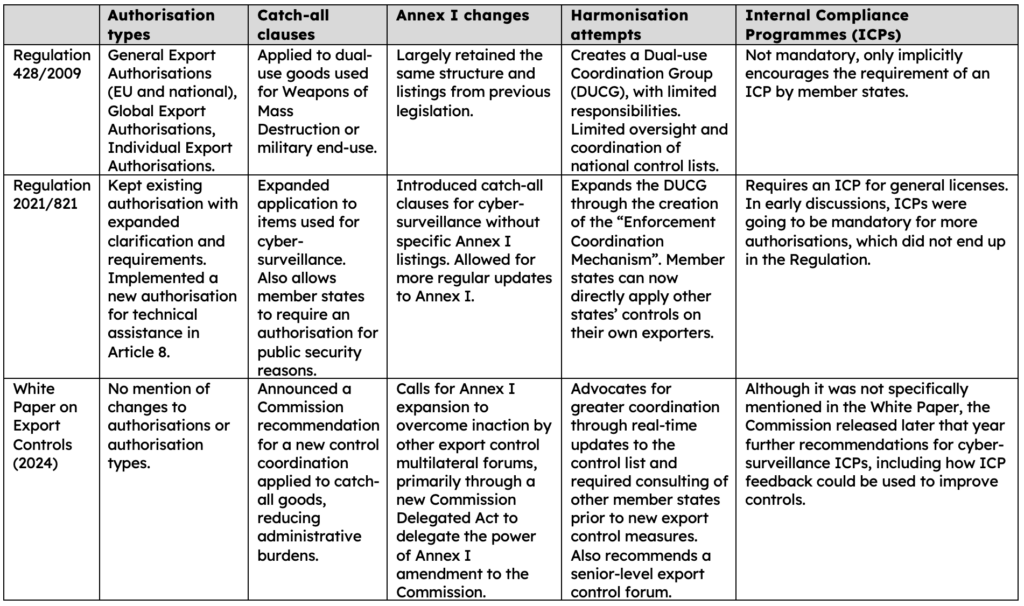

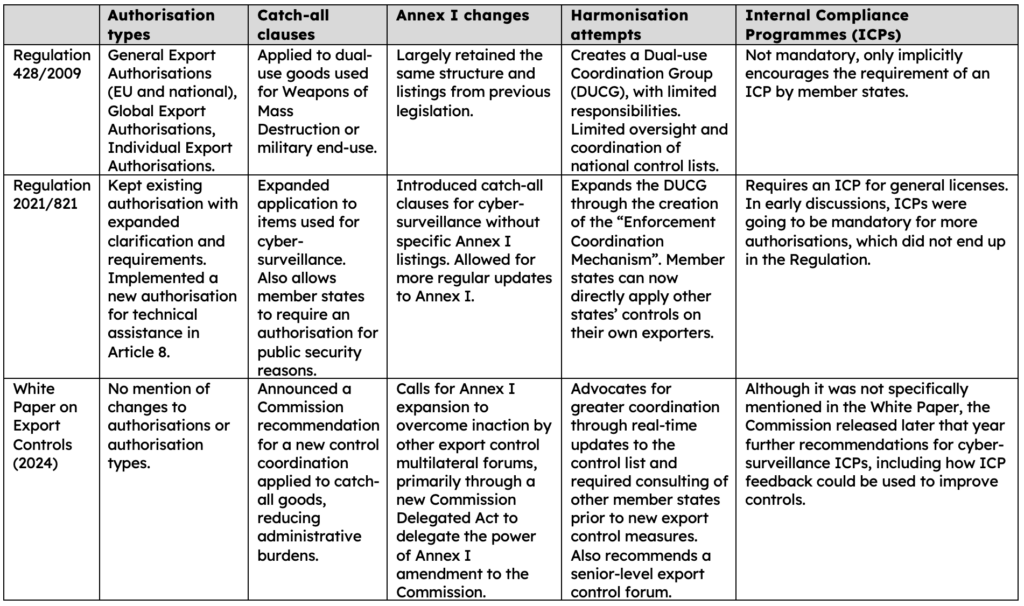

In 2009, the Council of the EU created Regulation 428/2009, a system of export controls meant to address vulnerabilities from certain dual-use exports: chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) materials; related technologies; telecommunications; and propulsion systems, among others. These regulations aligned the EU with various international agreements, such as the Wassenaar Arrangement, Chemical Weapons Convention and the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR). Since the passage of the previous export control regulation in 2000, Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Slovenia, Slovakia and Romania had joined the EU but were not party to the MTCR, and Cyprus was also not party to the Wassenaar Arrangement, creating gaps in enforcement. This new regulation would ensure that all EU member states were subject to the requirements of these international agreements and prevent unfair competition by member states that were not parties. The regulation created a system of authorisations for the export of dual-use goods, including:

- EU General Export Authorisations: allow for the export of certain dual-use goods listed in Annex I of the Regulation to Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland and the US;

- National General Export Authorisations: member states may issue authorisations for the export of Annex I goods (except for those listed in Annex II) if the country of destination is not already covered by an EU General Export Authorisation or under arms embargos, and the intended end user/use is not a risk;

- Global and Individual: member states may grant authorisations to specific exporters of dual-use goods to specific third-country end-users/uses with consideration towards intended end-use, potential risk, and relevant existing agreements and obligations.

However, the Regulation sought not to create a unified export control regime, which was too ambitious an objective at the time, but to put in place information-sharing requirements that allowed a given member state to examine all valid denials decided by others. Each member state had its own administrative, substantive, and operational approaches to applying Regulation 421/2009, leaving member states vulnerable to circumvention and differing requirements for catch-all terms. In 2011, the European Commission detailed in a Green Paper that the differences in export control regimes were at times so significant that specific exports could be expressly prohibited or heavily delayed in one member state while being freely exported in another.

Although Regulation 428/2009 was repeatedly amended over the following decade, it faced another challenge as it did not provide an adequate framework to address evolving threats in the areas of cybersecurity and surveillance, artificial intelligence, and other emerging dual-use technologies. In 2021, the European Parliament and Council created Regulation 2021/821, a recast of the dual-use export regulation. What resulted from trilogue negotiations between the Commission, Parliament, and Council was a new regulation that aimed to harmonise export control policies and address emerging technologies, but these changes still did not create a comprehensive common export control policy. During trilogue negotiations for the adoption of the Regulation, the main concerns of these governing bodies included: addressing exporter burdens and expanding upon or harmonising existing controls to account for cybersurveillance and emerging technology concerns.

Subsequent measures were unableto satisfactorily address these concerns. In the area of exporter burdens, while the Commission pushed for changes to the time limit for processing authorisation licenses and changes to the regulation of cloud computing services, member states prevented any real implementation, instead limiting the mandate of these reforms to a mention in the preamble, rather than concrete steps to be taken by appropriate authorities. Likewise, the Commission’s proposals for changes to harmonising export controls were limited in Regulation 2021/821. New “coordination mechanism[s]” were created to facilitate greater information sharing between agencies, and this allowed member states to adopt other member states’ national controls on unlisted items. Yet, this did not substantively address conflicting national regimes for export controls that could lead to circumvention and forum shopping.

Table 1 – Evolution of EU export control policy

Sources: Regulation 428/2009, Regulation 2021/821, White Paper on Export Controls, Commission Recommendation 2024/2659

Trending toward a common export control policy? The Commission’s “White Paper on Export Controls”

From its conception, the European Single Market has raised questions for policymakers on how to harmonise differing export requirements for both member states and third countries. However, attempts to fully synchronise export controls have been previously rejected. Ahead of the single market deadline at the end of 1992 and the beginning of the enforcement of the Maastricht Treaty, negotiations for the first iteration of a dual-use export control began that same year but were protracted until the adoption of a final resolution in 1994. During the negotiation, member states disagreed over whether such a policy would be subject to regulation as a trade issue or a foreign policy and security issue, complicating the extent to which measures could be passed to harmonise policies. Additionally, the purpose of passing export control policies was not primarily to protect the EU against emerging threats, but to further progress toward the Single Market and reduce misalignments that might impede that goal. Under the current framework, national governments “autonomously determine” how differences in export control principles and the assignment of authorisation licenses mandated by the EU are legislated and assessed.

However, in the eyes of institutional actors, the current geopolitical circumstances and the rapid advancement of technologies regulated calls into question the effectiveness of this framework. The 2024 White Paper on Export Controls is indicative of desires in Brussels to reshape the existing export control regime, potentially at the expense of national competencies. Importantly, any expansion of the export control regime of Europe will necessarily be separate from existing non-binding multilateral forums that could be used to guide the implementation of export controls. The EU is hesitant to use multilateral forums like the EU-US Trade and Technology Council, given its concern that the US will only act to maintain “technological superiority” over the long run. This next section will explore internal institutional efforts (such as through the publication of the “White Paper” and subsequent Commission recommendations) to reform export control policies by harmonising implementation and enforcement.

The expansion of the dual-use enforcement coordination group

In recent publications, policymakers have signalled their discontent with the current system of enforcement coordination that has resulted in uneven implementation of existing regulations. Many have specified that there are far too many actors trying to coordinate amongst each other to create an export control policy that is tailored to each member state’s exact needs and industries, while also being in alignment with the overall goals of export control regulations. Regardless of whether the Annex I list was comprehensive enough, that does not change the problem that enforcement is uncoordinated and leads to circumvention and forum shopping. To rectify this problem, export control competences could potentially be shared more broadly with the EU and its institutions, resulting in a supranational system of export controls.

The necessary framework for such an arrangement may already exist, as the seeds have been planted in Regulation 2021/821 and committee reports. In Regulation 428/2009, a DUCG was established to share best practices among member states. Then, in Regulation 2021/821, the DUCG established an enforcement coordination mechanism, mandating that member states work together to exchange best practices (Article 25.2). In 2023, a European Parliament committee’s draft recommendations suggested the creation of a “dedicated European Export Control Agency”, overseeing the Union’s dual-use export control regime. If a supranational system were to be implemented, it could be through expanding current mechanisms.

The 2021 Regulation and subsequent publications are likely to generate changes in three areas: 1) replacing the large number of national and supranational institutions responsible for enforcement with one single supranational institution; 2) overcoming existing uneven implementation; and 3) establishing procedures for how to uniformly and timely apply new regulations to anticipated emerging technology and cybersurveillance items.

The January 2024 White Paper on Export Controls has already proposed a solution to the latter two problems. The document advocates for creating a new dual-use regulation that would grant the Commission the ability to amend the Annex I list. This would ‘allow uniform controls throughout’ the Union and ‘increase the effectiveness of EU controls and the efficiency of controls across Member States’ by reducing the reliance on ‘legislative and regulatory resources in the Member States’.

In addition to the Commission, several business stakeholders – not least ASML – are willing to implement reforms. That said, important roadblocks remain. As previously mentioned, export control policy began as an institutional effort to aid in the completion of the Single Market, not to coordinate national competencies against threats from emerging technologies. Furthermore, the framing of export control policies as a security policy matter, not simply a matter of market governance. Security measures, under the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), are handled as intergovernmental issues, requiring the full consent of all member states. Importantly, France and Germany have so far preferred to pursue cooperation in export controls through ad hoc formats. The Future Combat Air System developed between the two countries, as well as Spain, for example, relies on a trilateral agreement that governs exports to third countries. Reacting to the Commission’s agenda-setting efforts, the French and German defence ministers have flatly stated that ‘the Commission has no role to play’ in export controls, an area that remains under the purview of national competences.

Conclusion

Since the passing of Regulation 428/2009, EU policymakers have shown their desire to expand and harmonise export control policies, granting more competences to institutions and creating a more coordinated approach to the export of dual-use technologies. This has resulted in a system of authorisations and requirements for EU member states to implement, although national governments ultimately retained the responsibility to interpret and implement these regulations. Since Regulation 2021/821, emerging technologies have been a new area of focus for export controls discussions, given member states’ dissatisfaction with the current framework’s ability to safeguard against growing geopolitical threats. The White Paper on Export Controls followed in 2024, prompting discussions over whether new regulations should be implemented, with greater competencies given to EU institutions. While the barriers to a common export control regime may be daunting (i.e., control harmonisation being viewed as a CFSP matter that requires unanimous consent, along with significant concerns by certain influential stakeholders), the political willingness and past precedent do exist for an expansion of EU competences. This Policy Brief has sought to evaluate how the existing proposals for a common export control policy would address implementation gaps and draw lessons from prior institutionalisation efforts. Although the case for a common EU export control policy is compelling in the current geopolitical context, major roadblocks remain, and progress is likely to proceed in a piecemeal manner.

__________

The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for Security, Diplomacy and Strategy (CSDS) or the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB).

ISSN (online): 2983-466X