CSDS POLICY BRIEF • 14/2025

By Joris Teer

21.5.2025

Key issues

- For the last three years, every time Washington tightens technology transfer restrictions or increases tariffs, Beijing points more economic weapons at the United States’ (US) defence industrial base.

- To hit the US where it hurts, China would likely have to halt or radically decrease critical raw material exports to almost all countries.

- Europeans have no control over the pace of US-China escalation. To protect itself, the EU should call a critical raw material emergency now and push all G7 and other partners to do the same.

Introduction

In response to President Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs, Beijing introduced export controls on even more critical raw materials. The pattern of the last three years is clear: every time Washington tightens technology transfer restrictions or increases tariffs, Beijing points more economic weapons at the US’ defence industrial base. China imposes these licensing requirements specifically on materials of which it dominates the mining or refining, as it did for heavy rare earths on 4 April 2025 in retaliation to US “Liberation Day” tariffs. But critical raw material embargoes are a blunt tool. To hit the US where it hurts, China would likely have to halt or radically decrease exports to almost all countries.

This puts Europeans in a bind. They have no control over the pace of US-China escalation, but a Chinese decision to proceed with retaliation would derail Europe’s rearmament and critical industries. At a time of sustained Russian aggression and uncertainty about US commitment to NATO, this is dangerous. To protect itself, this CSDS Policy Brief argues that the European Union (EU) should call a critical raw material emergency now and push all G7 and other partners to adopt maximalist policy packages too. Making use of their combined industrial advantages and market size gives the EU, the US, partners in the Indo-Pacific and others the best chance to bring production online before it is too late.

Beijing’s critical raw material weapon

In its tech and trade competition with China, Washington has focused on playing offence. China has used the entire post-Cold War period to build up its defences: namely, control over low economic value-added, but strategically indispensable industries like mining and refining. Beijing has combined state-subsidised overproduction and the shoring up of concessions abroad, with a high tolerance for environmental pollution. For specific materials, the Chinese government has strengthened its ability to flood markets and kill foreign competitors, as it consolidated material producers and created more direct state control over production volumes.

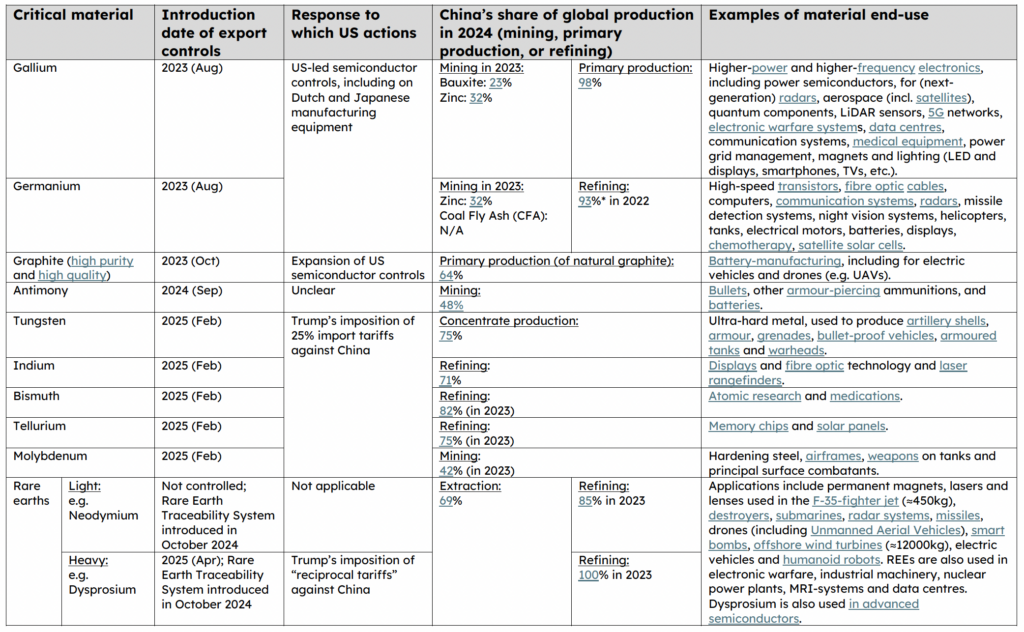

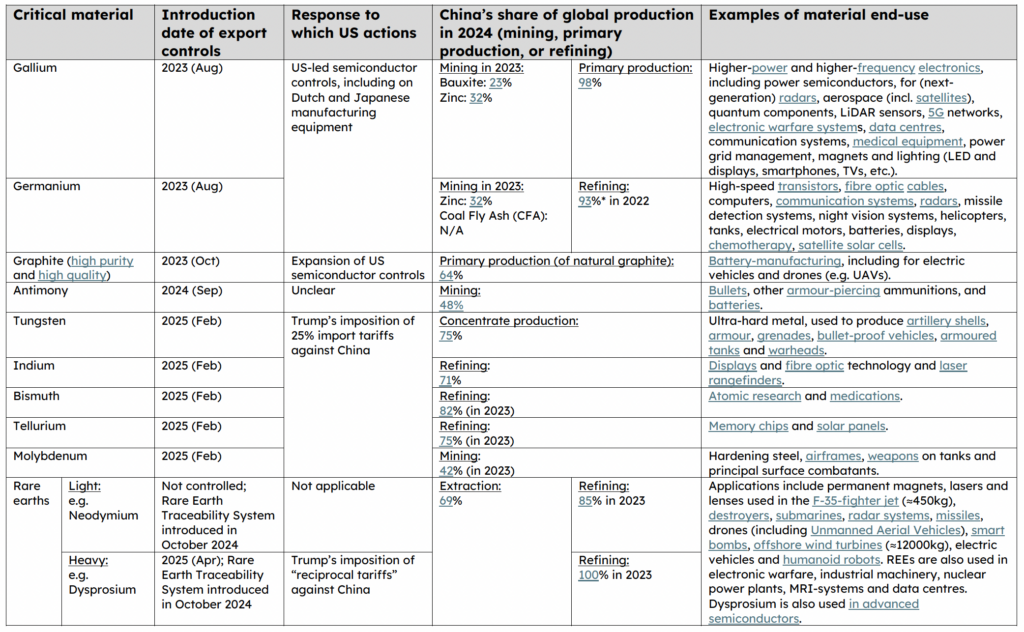

Every few months since August 2023, Beijing has pointed more economic weapons at US industries. First, China introduced export controls on gallium and germanium in response to US, Dutch and Japanese controls on semiconductor manufacturing equipment exports. These materials are used to produce radars, data centres, communication systems and many other vital end-products (see Table 1). Beijing sent a clear warning to the US and its allies: we have the ability to pull the rug from underneath your critical industries. Then, China reduced gallium and germanium exports across the board and halted exports to the US altogether. As a result, industries outside of China face twice higher gallium prices, putting them at a disadvantage. What remains of Japanese, European and other gallium stockpiles is all that stands in between these countries and shortages that would derail critical sectors.

Table 1 – Beijing’s growing weaponisation of critical material supply chains

Source: Joris Teer, 2025 (access a PDF version of Table 1)

China has answered subsequent US tech or trade moves consistently with export license requirements for more materials. Until now, these cover graphite, antimony, tungsten, indium, bismuth, tellurium, molybdenum and heavy rare earths. Without – often indirect – access to these materials that China controls, defence, medical, high-tech and other critical industries can barely produce anything. From the announcement of rare earth controls on 4 April 2025 onwards, industries around the world have held their breath to find out whether China will resume rare earth and permanent magnet exports. By mid-May, the Chinese government granted some licenses, including to Volkswagen, but exports remain far below 2024 levels. Even the best-case scenario is likely to threaten Europe’s security.

Three scenarios for China’s critical mineral coercion

Scenario 1: targeted attack, unpredictable fallout

China has only limited aims: disrupt the US military and 27 US military contractors. It seeks to achieve these aims by rejecting export licenses for specific military end-uses. After the heavy rare earth licensing period Beijing continues the supply to almost everyone else, including key commercial end-users in Europe.

Even this limited action would still likely lead to shortages in both the US and Europe, as limited stockpiles slowly run dry. First, an attempt to install a targeted boycott will hurt European security indirectly. US weapon systems, like the F-35 fighter jet, are used by both the US and European militaries to deter adversaries. The F-35 contains 450kgs of permanent magnets. China included these magnets, of which it controlled 85-90% of production in 2020, in its latest round of controls.

Second, China may decide that hurting US defence producers requires the targeting of US allies too. There is early evidence that Beijing threatens penalties against third country component manufacturers, like Korean producers of transformers, that supply US military end-users. Japanese and European manufacturers may be caught in the crossfire next: they make use of Chinese gallium to produce gallium-arsenide wafers. In turn, US manufacturers use these to produce semiconductors for wireless communications and other functions. Finally, these chips are used in a wide range of defence and civilian industries in the US, Europe but also China.

Beijing may decide that it needs to block supply to European wafer manufacturers, in order to disrupt US defence production with European defence and civilian industries as collateral damage. Worryingly, China – already the largest semiconductor manufacturer in the world – is rapidly expanding its ability to produce all kinds of chips, whereas the US and EU still fail to produce gallium. President Xi has more strategic space to halt supplies each year: China is de-risking its dependence on the US and EU manufacturing much faster than vice versa.

Third, the wide variety of rare earths and components that China’s controls cover, and the uncertainty about the material make-up of these components, are likely to overwhelm Chinese customs officials. If so, this will lead to further delays and therefore a reduction in material supply.

Scenario 2: untargeted attack, colossal fallout

If China’s goal is to hit the US military as hard as possible, Beijing has to radically reduce or altogether cease exports to (almost) all other countries. Just a reduction would be dangerous enough: one model projects that decreasing gallium exports by 30% could already diminish US economic output by US$602 billion, or 2.1% of US Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This would derail US and European industries and therefore weaken deterrence in Europe and Asia. China may well continue material exports to Russia to ensure the Kremlin’s defence production proceeds without delay.

There is a strong rationale for Beijing to opt for an untargeted attack. In scenario 1, Beijing’s critical materials would likely continue to end up in the US via third countries, albeit at reduced volumes. We have seen this before. The Kremlin has maintained access to micro-electronics through illicit trade networks, despite all the main semiconductor producing countries – except for China – adopting an incredibly stringent sanctions regime. The Chinese government has studied these sanctions and Russia’s response carefully. Likewise, Taiwan’s TSMC, the world’s leading semiconductor manufacturer, has failed to prevent Artificial Intelligence (AI)-chips from ending up in China, despite US controls and frustration.

China is aware that not all dependencies are equal. Boycotts of material supplies, unlike connected complex products, cannot be imposed with precision. The US and the Netherlands were able to block exports of ASML’s unique Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography systems to China, without affecting the company’s exports to other countries. The reason: these machines have to be transported in multiple jumbo jets and depend on a lifetime of servicing and spare parts after delivery. Instead, critical raw materials and semiconductors have independent lifespans of decades.

Scenario 3: multiple front attack, existential fallout

It would be unwise, however, to assess the threat of China imposing critical material controls in isolation. Tensions in East Asia have risen rapidly: China has modernised its armed forces, expanded its military exercises around Taiwan and stepped-up its grey zone warfare. In the case of a US-China diplomatic fallout or even a military confrontation over a blockade or invasion of Taiwan, Beijing would almost certainly halt critical raw material exports altogether. Its primary motivation would be to ensure vital industrial, state and societal functions, by hoarding all of its vital resources for at least until the end of the conflict. This would likely include critical materials, medical supplies and a wide variety of legacy chips.

However, Beijing’s actions in this scenario would also have an offensive purpose. China would likely use all means available, including material dependencies, to sabotage US and allied attempts to mass-produce new weapon systems, crucially drone swarms and ammunition. This would almost certainly be the case if the US Navy does come to Taiwan’s aid. The First and Second World Wars provide lessons: respectively 96% and 97% of trade between direct adversaries disappeared. This would be devastating for the US and Europe in a long conflict, as production capacity continues to matter during a war. The US Navy grew from just under 400 ships in 1939 to almost 7,000 in 1945.

The risks for Europe are not just economic. If the US is involved in a conflict in East Asia, the US will prioritisesupplying scarce ammunition and weapon systems to the Indo-Pacific over maintaining deterrence against Russia in Europe. Finally, even if Beijing would be willing to continue exports, fighting throughout the Western Pacific may make this impossible.

A critical raw material emergency: united we stand, divided we fall

The short-term critical raw material future of both the US and EU looks bleak. They should prepare for the worst: China-US trade talks may have resulted in a pause on the highest tariffs, but China only promises to ‘suspend or remove the non-tariff countermeasures’ taken ‘since April 2, 2025’. This suggests that China may at best remove controls on heavy rare earths and related components. After all, Beijing adopted the controls on all other materials prior to 2 April. But even for heavy rare earths, if China brings back exports to 2024 volumes, there is no guarantee of long-term supply. China can flexibly tighten or loosen the thumb screws (or in other words, switch between scenario 1, 2 and 3) continuously and without warning. This gives Beijing leverage to deter or compel the US and EU on trade, tech and even military security issues.

Even together, the G7 and other partners will face plenty of obstacles to take the critical raw material bullet out of China’s gun. Globally, it takes an average of 15.7 years to open new mines and producers outside of China lack key technologies, for example to refine materials. Furthermore, most liberal democracies have adopted stringent climate targets that sit uneasily with emissions-intensive activities like mining. They are also allergic to the industry’s environmental drawbacks. Beijing’s measures to thwart US and EU de-risking strategies, such as banning the export of technologies to extract, process and make magnets out of rare earths, further complicate the issue.

Europe cannot sidestep Beijing’s critical raw material retaliation, nor does it have any control over the accelerating pace of US-China escalation. Regrettably, the EU’s own policies to mitigate material-related risks are moving far too slow. The US has booked limited, but more successes – like reopening the Mountain Pass mine – and is better placed to onshore material value chains, for example because of 4-to-5 times lower natural gas prices. The Trump administration is racing ahead with executive orders to open-up federal lands, cut environmental constraints and it even weighs-up making Chinese materials artificially more expensive through tariffs. But the US does not have the geological deposits or all of the technologies to go it alone.

Other partners, like Japan and Australia, have accomplished more too. Japan learned lessons from a 2010 crisis in the East China Sea, during which China temporarily halted rare earth exports to its industries. Its state investment and expertise vehicle JOGMEC has led the way in developing mining and refining concessions abroad, including by sponsoring rare earth extraction by Australia’s Lynas. The EU has things to offer too: it can leverage its important mid-stream expertise in chemicals and the enormous demand it creates for raw materials through its energy transition and rearmament to spark new supply outside of China.

Displeasure in European capitals with the first months of the second Trump administration, particularly its rhetoric and actions on trade and Ukraine, is understandable. But alone, the EU, US or others will be too slow to create sufficient volumes and diversity of non-China supply that is already needed today. The near-term threat is simply too great. Calling a critical raw material emergency, and pushing partners to adopt maximalist policy packages too, gives Europe the best chance to save its industries.

Policies should include use of defence funding to kickstart production, cutting permit procedures and financially supporting key partners like JOGMEC to exchange knowledge and technologies. Once sufficient supply outside of China has come online, these countries should include “buy-trusted-partner”, instead of “buy-European”, clauses in government tenders, for example for wind parks. This is a big gun: public procurement makes up 14% of GDP in the EU. Preferential treatment for materials from trusted countries, perhaps even combined with tariffs on Chinese materials and components, can ensure that material producers outside of China have sufficient demand for their products.

Because of new trust issues in transatlantic relations since the second inauguration of President Trump, the EU should bring online much more material production domestically too. The risk that the US uses economic sanctions or high-tech dependencies to force the EU to accept an unsustainable “peace” in Ukraine is the most pressing challenge. However, many of the EU’s 47 strategic projects to boost material production under the Critical Raw Materials Act will bear fruit only throughout the 2030s. Their success is not guaranteed: mass funding must still be allocated, permit times need to be actually reduced (not just on paper) and investments must be protected against Chinese dumping. Before then, the transatlantic partners rely on each other to fix this problem together, whether they like it or not.

__________

The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for Security, Diplomacy and Strategy (CSDS) or the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB).

ISSN (online): 2983-466X