CSDS POLICY BRIEF • 9/2025

By Salih Bora, Mary E. Lovely and Luis Simón

2.4.2025

Key issues

- The United States’ sweeping trade tariffs have led to much uncertainty about the future of the global economy;

- The short-term outlook for transatlantic cooperation to combat Chinese over-capacity is bleak;

- There is a great risk that all three major economies are pulled into a spiral of subsidies and trade-distorting measures.

Introduction

President Donald Trump’s 2 April 2025 announcement of a sweeping tariff hike on all US trade partners led to much uncertainty about the future of the global economy. Such uncertainty was partly assuaged by Trump’s subsequent decision to pause many of his tariff threats – including the ones affecting the European Union (EU) – barely a few days thereafter. China was not affected by Trump’s pause, however. The fact that President Trump has raised tariffs on China by 145% since taking office on 20 January heralds what many have referred to as an all-out US-China trade war.

Although it goes far beyond the policies of previous administrations, this paradigm shift builds on longstanding US concerns about Chinese non-market over-capacity. China’s trade surplus with the world soared to a record-breaking US$992 billion in 2024, a 21% increase from the previous year. Through November 2024, the United States (US) purchased US$3 worth of goods from China for every US$1 of goods sold to China in that year. The EU purchased US$2 worth of goods and services from China for each US$1 of goods sold. China’s average export prices in 2024 were lower each month than in the year before, according to the monthly export price index, which has remained below 100 since June 2023.

Concerns about China’s exports have intensified over many years, reflecting the intense competitive pressures on producers and compelling American and European policymakers, government officials and political leaders to try to counter-act them. President Trump’s decision to raise tariffs on China by 145% is the most recent – and arguably most dramatic – example of broader concerns about Chinese over-capacity.

The roots of this problem are systemic, not cyclical, though the trade imbalances are significantly exacerbated by China’s low internal demand and prolonged recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. At heart, there is a clash between China’s party-state capitalism and the free-market principles underpinning the – Western-led – global economic order. China’s integration into the rules-based trading order, particularly its admission to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001, encouraged its industrialisation and exports, enabling China to grow at a historically unprecedented pace. Contrary to expectations and hopes that prevailed in the 1990s and 2000s, China’s integration into the global trading system was not accompanied by a convergence of Chinese institutions with their Western counterparts. The adherence of Chinese party-state capitalism to the global trading order was incomplete, involving breaches of numerous multilateral rules on intellectual property, state support and subsidies for industrial expansion, and other concerns raised by China’s trading partners.

Today, this clash is particularly evident in sectors that US and European leaders have deemed essential for growth and security, charging that Chinese industrial subsidies, rather than comparative advantage, are the basis for the country’s export success. The Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (ASCM) of the WTO, which took effect in 1995, has failed to address these tensions. However, the EU and the US have taken different approaches to resolve them. The EU seeks, at least for now, to preserve and adhere to global trading rules. By contrast, the US has acted unilaterally –even before the second Trump administration – to defend its domestic production by engaging in a trade confrontation with China that, together with China’s retaliation, has rattled global financial markets.

This Policy Brief explores these EU-US divisions, their reflection on trade and industrial policy and prospects for cooperation. We begin by briefly exploring the concept of “non-market over-capacity”, arguing that the concept lacks a common definition, but that EU and US policymakers have concluded that Chinese over-capacity poses an unacceptable economic security threat. Secondly, we show that, despite this common diagnosis, the EU and the US differ in how they weigh alternative remedies, notably the design of industrial policies to support domestic producers and trade barriers to hinder Chinese market penetration. Moreover, EU-US discrepancies in industrial and trade policy are compounded by a further layer of disagreement among EU members. These circumstances seriously undermine the effectiveness of both blocs’ response to non-market over-capacity. On the one hand, the US impetus to find a unilateral solution does not address the pressure from Chinese exports but merely channels them to the rest of the world – including to Europe. On the other hand, transatlantic disagreement creates wedging opportunities for China.

In the light of these shortcomings and amidst the second Trump administration’s threat to instate “reciprocal tariffs” on Europe, we discuss options for coordinated action against Chinese over-capacity. We argue that the EU can take the lead toward a resolution within the rules-based system while maintaining an open door to future US participation.

Diagnosing the non-market over-capacity problem

National security concerns about over-reliance on China for essential goods and fear of further industrial hollowing have combined to spur actions designed to defend and promote domestic production. These policy initiatives reflect a new focus on the security implications of China’s rising competency in semiconductor fabrication, artificial intelligence and new energy equipment. They also embody a common belief that China has “cheated” its way to the top through state intervention to promote new and emerging sectors.

Effective action to combat “non-market over-capacity” is hindered by a lack of consensus on what constitutes “non-market” activity and on what constitutes “over-capacity.” Fractures even within the Western alliance are evident in efforts to reform rules that discipline state subsidies. Within the WTO system, a subsidy is a ‘financial contribution by a government or any public body’ that ‘confers a benefit’ on the recipient. As described by Bown and Hillman, over time this definition has proved inadequate to adjudicate disputes involving subsidies provided by state-owned enterprises and other cases where the line between the government and private sector is blurred. Attempts to change the system have not resulted in formal reform proposals, in part because of differences in how stricter rules might affect countries that have significant state sectors.

Over-capacity is also a complex concept to define and difficult to measure. For some, a key indication of over-capacity is industrial capacity utilisation, but utilisation rates vary over time and across sectors for many reasons, including with the business cycle. Alternatively, and with a focus on the implications for foreign producers, Al-Haschimi and Spital define over-capacity as output that cannot be absorbed domestically at current prices. However, supply increases and declining prices may also result from conditions other than non-market actions, such as a country’s ability to harness economies of scale, allowing marginal cost to fall as output rises. In defending its growing exports of electric vehicles (EVs), China has relied on alternative explanations of its export success to rebut accusations of over-capacity from trading partners.

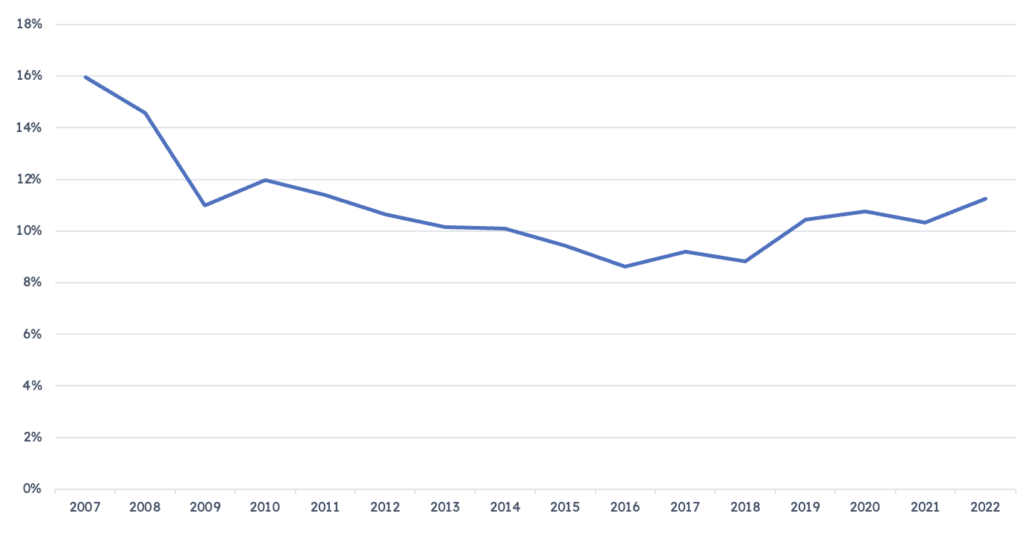

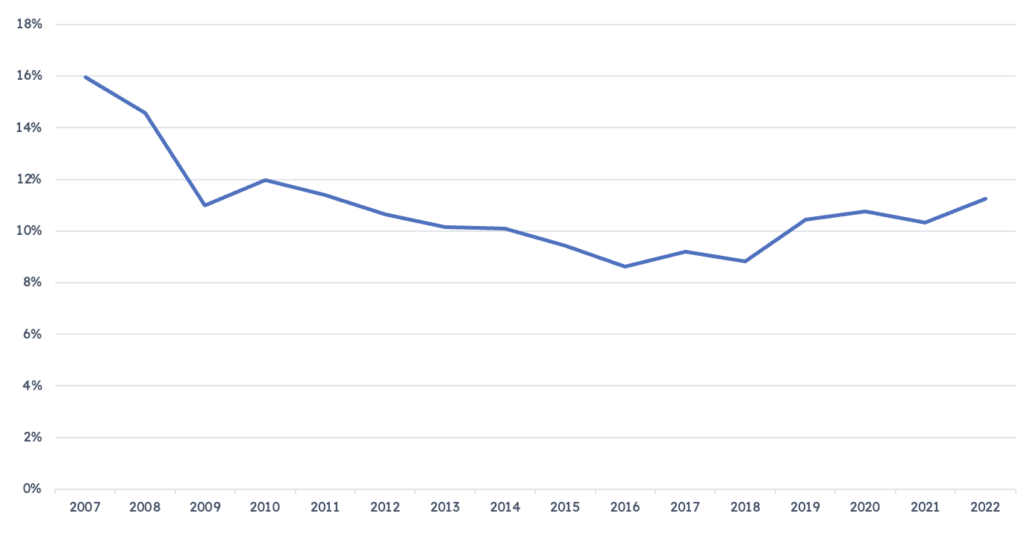

Whatever the reasons for China’s rising prowess in specific industries, in the aggregate its macroeconomic imbalances are worsening. As seen in Figure 1, while Chinese productive capacity grew rapidly after its entry to the WTO, its domestic consumption grew more quickly, resulting in a declining share of exports in GDP and no evidence of aggregate over-capacity. Importantly, however, this long-term trend reversed around 2017 and Chinese exports as a share of GDP have risen in the years since, consistent with Western claims of a growing over-capacity problem. These imbalances are most acute in the manufacturing sector.

Figure 1: China’s manufacturing exports as a share of domestic production, 2007-2022

Source: Asian Development Bank, China’s National Input-Output Table

This diagnosis of a “China problem” is shared across the two sides of the Atlantic. US administration officials and the European Commission agree that China’s growth model is generating non-market over-capacity and harmful export surges. With political fragmentation often blamed on China’s integration into the global economy and the subsequent loss of manufacturing jobs, there is strong support to “do what it takes” to avoid a similar fate in newly emerging sectors.

While past experiences with Chinese over-capacity animate the urgency with which EU and US policymakers approach the problem, recent experience in the photovoltaic (PV) solar equipment shows uncoordinated responses can be ineffective and end with a “divide and conquer” outcome. China’s share of global PV solar production rose from 1% in 2001 to 59% by 2010, most of it for export. This rapid success brought intense competitive pressures to manufacturers outside China and led to considerable trade frictions with both the US and the EU. In 2012, the US imposed duties of 24%–36% on imported panels made from Chinese solar cells after concluding that Chinese solar companies had received unfair subsidies and dumped products on the American market. In June 2013, based on similar complaints, the EU imposed modest tariffs of 11.8% on solar panels imports worth five times as much as the American volume, but these duties were removed after the Chinese and the EU agreed on a price floor and an import quota for Chinese modules. In July 2013, and in what many see as retaliation, China levied duties exceeding 50% on solar-grade polysilicon imports from the US, ultimately bankrupting one of two major American polysilicon producers. China is now the world’s leading polysilicon producer, while Germany remains the largest exporter of polysilicon to China. China now has a near-complete monopoly in PV solar, with a global market share between 75% and 95% across the different components of the value chain.

EU-US responses: similar tools, different approaches

The EU and the US, proceeding from a similar diagnosis of the problem concerning China’s growth model, have responded with trade policy and industrial policy measures. Over the past 8 years, both have expanded the use of industrial policies to support key sectors and levied tariffs on Chinese imports of targeted goods. Despite similarities in response, these measures were implemented in an uncoordinated manner and with different attitudes toward compliance with WTO subsidy rules.

For the US, tariffs have become a key tool to combat Chinese unfair trade practices. In 2018, the Trump administration launched a trade war with China, resulting in average bilateral duties on imports rising to roughly 20%, with new tariffs and counter-tariffs covering more than 50% of bilateral trade by the end of 2019. Acting unilaterally, these China tariffs were also accompanied by a set of tariffs against many close allies, including the EU, fuelling animosity in bilateral trade relations. The abandonment of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations for a free trade agreement with the EU signalled a move further away from cooperation toward unilateral US action.

Coming to office in 2020, the Biden administration attempted to de-escalate bilateral trade tensions with the EU through temporary agreements on aviation and steel and aluminium and the creation of an EU-US Trade and Technology Council (TTC) to coordinate on those areas and on China policy more broadly. Many saw the agreements on aviation and steel and aluminium as temporary ceasefires and questioned the reach of the TTC, while bilateral trade negotiations (TTIP) remained in the deep freezer and with few prospects of revival.

On China, the Biden administration maintained many of Trump’s first-term tariffs and even escalated the tariff war with China, not least by providing significant subsidies through the Inflation Reduction Act and additional tariffs, notably on EVs. Under President Biden, the US added to the export controls enacted under the first Trump administration, expanding lists of sanctioned Chinese firms, and prohibiting the sale to China of advanced semiconductors and semiconductor manufacturing equipment. These actions have significant implications for firms based in the EU. As of the publication of this Policy Brief, President Trump has made good on his threats in the 2024 campaign to raise tariffs even more on China. Trump administration officials have most recently declared that they have raised tariffs on China by 145% since taking office in January.

While it is almost certain that some bilateral communication about these US actions occurred, the actions were taken unilaterally and without coordinating policies enacted by the EU. Trump’s plans for “reciprocal” tariffs on Europe and other trading partners were paused in response to market disruptions in April 2025, but the prospect of more tariffs remains. An important cleavage in transatlantic coordination is that the EU response is premised on the assumption that economic cooperation with Beijing is still possible, while US actions have progressively eliminated this possibility even prior to the “Liberation Day” tariffs. On EVs, for example, the Biden administration levied a prohibitive 100% tariff, and banned the use of Chinese and Russian technology in connected cars sold in the US. In contrast, the EU sought to level the playing field with tariffs ranging from 35% to 45% while maintaining market access for EVs produced in China. Furthermore, Chinese firms continue to be granted access to EU supply chains as part of an EU strategy to transfer know-how and technologies.

Overarching these actions is significant transatlantic divergence in the role of multilateral solutions to the current crisis. The first Trump administration (2017-2021) launched an attack against the multilateral trading system, convinced that it was unsuited to deal with the challenges posed by China, especially over-capacity and lack of market access. To prevent China from ‘gaming the international trading system’, the US started blocking appointments to the Appellate Body of the WTO in 2019, a policy that the Biden administration (2021-2025) continued. Although the US and the EU share many of the same concerns about the WTO, this mode of response was perceived negatively in Brussels. The EU joined other WTO members – including China – in instating a Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA), a temporary mechanism mirroring the functioning of the Appellate Body.

The other key defensive tool against Chinese overcapacity is industrial policy, also a site of transatlantic friction. Disagreement over the WTO was compounded by the implementation of the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act in August 2022. An important impetus for the Inflation Reduction Act was China’s growing dominance in new energy equipment, particularly EVs, but it contained funding and rules that favoured US producers over foreign producers. When passed in 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act was expected to direct nearly US$400 billion in federal funding toward clean energy, with the dual goal of lowering carbon emissions and ensuring America’s global economic competitiveness in autos, energy and related activities. In addition to a mix of tax incentives, grants and loan guarantees, the legislation includes domestic content requirements for EV components and assembly to make them eligible for consumer subsidies.

The Inflation Reduction Act has been met with deindustrialisation anxiety across the EU. Local content requirements are perceived as a threat for EU-based EV manufacturing as it incentivises businesses to move production across the Atlantic for market access. EU authorities even contemplated starting a WTO procedure against the Inflation Reduction Act. However, the Biden administration was receptive to EU concerns and an EU-US Inflation Reduction Act task force was created in October 2022, leading to ‘tweaks’ to the Act including the waiving of many requirements for leased vehicles. EU EV exports, an industry expected to be hit particularly hard by the Inflation Reduction Act, continued to grow after the Act was implemented. Nonetheless, the Inflation Reduction Act contributed to a shift in momentum toward EU proponents of vertical industrial policy – targeted measures – and the relaxing of state aid rules.

The EU’s response to the challenge of Chinese over-capacity – and no less significantly, to US unilateralism – included reform of competition policy, and in particular, state aid rules for enabling a more activist industrial policy. The Important Projects of Common European Interest (ICPEI), a state aid exemption based on Article 107.3 (b) of the Maastricht Treaty but codified in 2014, was extended into a broader range of sectors. The General Block Exemption Regulation (GBER), first instated during the 2008 crisis, has similarly been broadened into sectors such as renewable energy and green mobility. Finally, the EU level Temporary Crisis Framework (TCF), agreed upon during the COVID-19 crisis, was transformed into the Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework (TCTF) in March 2023. These instruments have enabled member states to implement vertical industrial policy measures that had previously been prohibited by EU competition policy because they would distort the Single Market. These rule changes allowed projected EU subsidies to reach a size comparable to the Inflation Reduction Act.

Reform of state aid rules has affected member states rather unevenly and, as a result, has led to intra-European tensions. A small number of member states, most evidently Germany, have fiscal resources that allow them to extensively support their industries. For the TCTF instrument, Di Carlo, Eisl and Zurstrassen estimate that Germany accounts for as much as 52% of total aid provided in the Single Market, followed by Italy (28%), Spain (9%), Hungary (3%) and Romania (3%). Similarly, Lopes-Valença and Lavery estimate that up to 80% of all aid allowed under the IPCEI instrument was allocated by Germany, France and Italy, with Germany alone accounting for 55%. Groups of member states have repeatedly warned the Commission that relaxing state aid rules promotes fragmentation of the Single Market, and to an intra-EU subsidy race.

Developing common fiscal capacities has been highlighted as a possible solution to these shortcomings, notably by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, who proposed a ‘European Sovereignty Fund’ during her 2022 State of the Union address. However, proposals to “Europeanise” national subsidies did not elicit much support from member states. While the current coalition agreement in Germany suggests that opposition from Berlin may not be as categorical as before, a genuine pooling of EU fiscal capacities is still a distant prospect. As things currently stand, a global subsidy race presents risks to the EU polity due to the fragmentation it creates within the Single Market. However, as illustrated by the 2024 Draghi Report on the future of European competitiveness, economic decline increasingly is seen as a far more existential threat. Moreover, the Trump administration’s “America First” trade policies dissipate remaining hopes that the turbulence surrounding the global rules-based order will be resolved soon. Under these circumstances, industrial policy initiatives are unlikely to slow down, with or without common fiscal capacities.

Is there room for transatlantic cooperation on China?

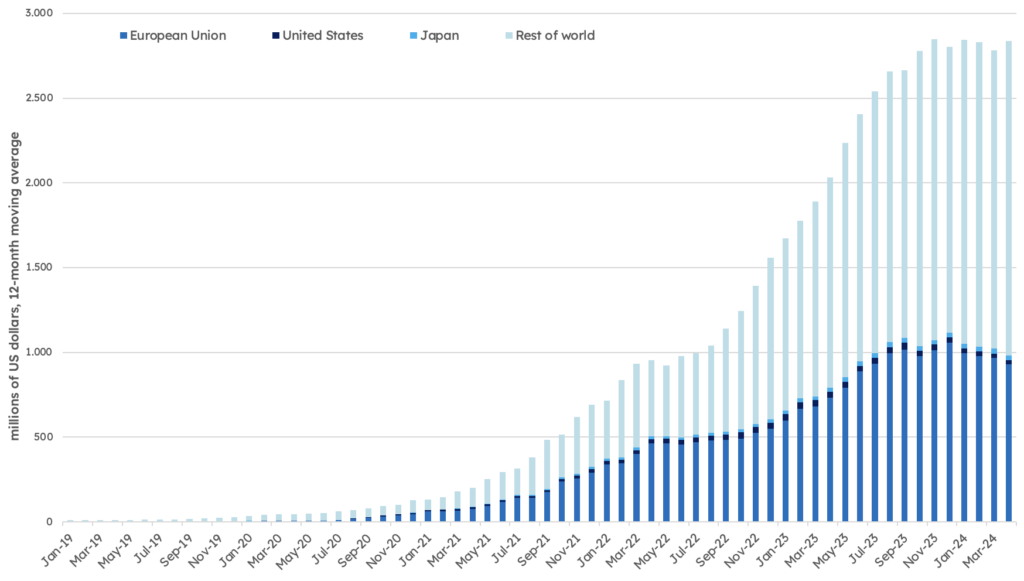

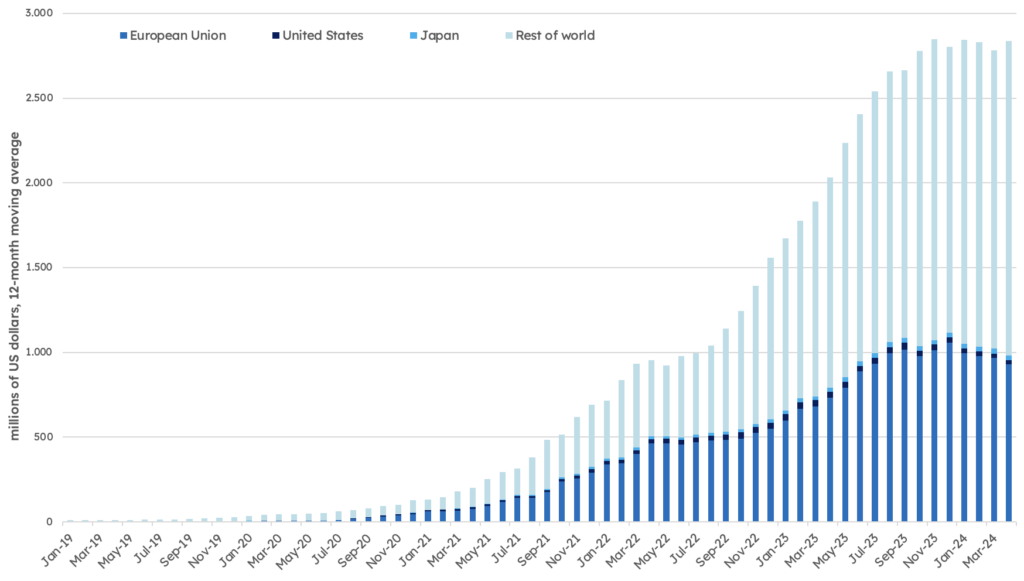

Readily available lessons from the past warn of the ineffectiveness of uncoordinated responses to Chinese export surges. Looking forward, the dangers of US unilateralism and EU internal division are evident. Consider recent developments in the EV sector, where the US and the EU have chosen fundamentally different approaches to the challenge of maintaining a domestic auto sector. As the US deflects Chinese EV exports through domestic investment, domestic sourcing rules, high tariff walls and bans on Chinese technology, the EU struggles to protect its domestic producers using countervailing duties that faithfully reflect its WTO commitments. As seen in Figure 2, as Chinese EV exports have risen 10-fold over the past three years, about one-third now land in Europe. In contrast, very few have been exported to the US or to Japan. As current US tariffs on China are high enough to bring bilateral trade to a halt – with the exception of smartphones and computers temporarily exempted by the Trump administration –, the pressure on European industry will only exacerbate.

Figure 2: Value of Chinese exports of electric vehicles, by destination

Source: Eurostat; UN Comtrade; China Customs. The HS870380 ‘vehicles; with only electric motor for propulsion’ is selected to calculate trade in electric vehicles.

Despite the Trump administration’s interest in rebalancing the EU-US relationship under threats of unilateral tariffs, the drivers for greater transatlantic coordination on China are compelling and go well beyond responding to over-capacity. To date, however, America’s unilateral, confrontational strategies have not prompted China to rebalance its growth model by stimulating internal demand. On the contrary, economic restrictions reinforced factions within the Chinese leadership who prioritise productive investment on the grounds of achieving national security and self-sufficiency. Moreover, the cost of decoupling from China will rise as its magnitude grows as will the value of transatlantic cooperation as US businesses look for alternative export markets and input suppliers. Additionally, without cooperation with allies, US export controls and technology restrictions strategy cannot work.

On the European side, security needs make continued cooperation with the US an imperative, a fact unchanged by the launch of bilateral US-Russia negotiations on the Ukraine war. Attempting to create a strategy outside of the transatlantic framework is likely to promote internal disarray in Europe. The preferred option for the EU would be to revamp coordination on China – whether in the context of the TTC or some new body – ideally as part of a broader transatlantic bargain including security. That said, in the current political environment it is difficult to see viable pathways for EU-US cooperation to combat Chinese over-capacity.

In the interim, the EU will hedge as it navigates instability in its relations with both the US and China. Europe is not without options for coordinating with other WTO members, many of whom also bridle under the weight of Chinese over-capacity. As it did during the first Trump administration, the EU could continue to pursue a rules-based system that includes China. However, the situation in 2025 is dramatically different from the 2016-2020 period. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, growing Chinese assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific and the challenge of non-market over-capacity considerably complicate cooperation with China. With member states more alert to security threats from China, any successful effort would require tighter rules on Chinese – and other countries’ – subsidy use and greater powers of enforcement and trade defence. Such a prospect can only succeed by maintaining European unity while gaining acceptance by China itself. One possible avenue for such a “grand bargain” may be to limit Chinese exports of strategic products while guiding Chinese investment and technology transfer to member states within the bloc.

To avoid exporting the China over-capacity problem to other nations – as the current US tariffs certainly will –, such a grand bargain could encompass not only the EU but the broader US alliance network, including Japan and South Korea. US allies can use the US-led alliance system to secure autonomy from a protectionist United States while, at the same time, reinforcing their hand against China. The vehicle for such cooperation could be through European participation in an existing alliance, such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership, or through a web of existing and new trade agreements.

Over the longer term, the benefits of creating economies of scale across the Atlantic are large. As we face the prospect of four years of potentially tumultuous transatlantic relations, it is important to remain open to better ways to navigate the new geopolitical reality. The EU and the US share the largest trading relationship in the world and enormous bilateral investments. Leveraging these ties through coordinated commercial and industrial policies can allow both the EU and the US to achieve considerable efficiency gains through scale economies and make the best use of their technological and industrial capabilities.

The key challenge ahead for the EU and the US is to find venues for cooperation to prevent their economic relationship from spiralling into a geoeconomic security dilemma. This is especially true because, apart from being members of the WTO system – which is itself increasingly fragile –, there is no binding framework that governs the trade and investment relationship between the EU and the US. So far, the TTC, created in 2021, has emerged as the only formal mechanism for EU-US cooperation on trade and is widely described as having under-delivered. The Council is a clear downgrade compared to the TTIP, as it presents a less ambitious form of cooperation based on soft law and prioritising executive-to-executive exchanges. While the TTC did achieve some partial successes, notably by creating common standards in areas such as 6G and semiconductors, its role in trade has been limited.

For both the US and Europe, the stakes are high. In a worst-case scenario, lack of EU-US cooperation can lead to a three-pronged trade war between rival blocs. Confronted with such a scenario, the already fragile unity of the EU could crumble completely. The EV tariff on Chinese vehicles, for instance, was the result of a close vote with 12 approvals, 10 abstentions and 5 against. It is noteworthy that Germany, the EU’s largest member state, voted against, along with central European member states that are part of the German automotive supply chain. Renewed transatlantic trade tensions – for instance, a US tariff on European EVs – could allow China to wedge EU member states and prevent a cohesive approach. Moreover, it would reinforce proponents of a “Fortress Europe” approach advocating greater distance from the US.

Weak internal demand and a seeming unwillingness to effectively discipline supply are further accentuating the Chinese macroeconomic imbalances that fuel its non-market over-capacity. The short-term outlook for transatlantic cooperation to combat Chinese overcapacity is bleak. EU and US responses, if similar to those of the last 8 years or, as recent events suggest, even worse, will pull the world’s three major economies into a spiral of subsidies and trade-distorting measures. Although bleak, the current deterioration of the rules-based order can be reverted or, at least, mitigated, if the EU works with like-minded partners within the US alliance network to begin reforms of the rules-based system. Meanwhile, given the long-term value of transatlantic cooperation, pathways for EU-US communication must remain open, even in the context of potentially divisive US action.

__________

The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for Security, Diplomacy and Strategy (CSDS) or the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). This Policy Brief is a revised version of the paper presented at the conference on Transatlantic Perspectives on US-China Geoeconomic Competition in Washington, DC, on 29 January 2025, jointly organised by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) and the Centre for Security, Diplomacy, and Strategy (CSDS) at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel. A version of the paper can be found on the PIIE website too. The authors gratefully acknowledge insightful comments from Chad P. Bown (PIIE), Jeffrey Anderson (Georgetown), and participants in the PIIE-CSDS conference. The authors also acknowledge support from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 101045227).

ISSN (online): 2983-466X