CSDS POLICY BRIEF • 24/2025

By Gesine Weber

17.9.2025

Key issues

- The European Union (EU) has multiplied its security and defence partnerships (SDPs) in recent years, mostly with partners in Europe and the Indo-Pacific;

- SDPs can strengthen cooperation with partners outside the EU on issues like defence industrial cooperation, readiness and more. Nevertheless, the scope of these partnerships clearly depends on political will and does not compare to a formal alliance;

- These partnerships will become increasingly important for the EU in the future as they allow like-minded partners to build ties, especially for middle powers caught between Sino-American competition.

Introduction

When the EU published its Strategic Compass, a plan for strengthening the EU’s security and defence policy until the end of the decade, in early 2022, an entire section of the document was dedicated to partnerships. Besides stepping up engagement with and in other international organisations, a key pillar to strengthen cooperation with partners outside the EU was a new approach to bilateral partnerships with like-minded partners. Security and Defence Partnerships have been the “underdog” of the Strategic Compass, at least in terms of public visibility. Compared to the “act”, “invest” and “secure” chapters, which focus, among others, on defence spending, capability development or joint action through missions of the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). Concluding the Strategic Compass on “partnerships” does, at first glance, not look like a game-changer for EU security policy. Nevertheless, these partnerships should not be underestimated because they can contribute to levelling up the EU’s action as a security and geopolitical actor.

Until August 2025, the EU has signed eight SDPs, mostly with states in Europe and the Indo-Pacific (by date of signature): Norway, Moldova, South Korea, Japan, Albania, North Macedonia, the United Kingdom (UK) and Canada. Additionally, a partnership with Australia is currently being negotiated, and exploratory talks with Switzerland started in June. Given the rapidly growing ties and enhanced exchanges between Brussels and New Delhi, another SDP with India can be expected in the future. Importantly, the SDPs do not constitute formal alliances or impose obligations for mutual defence or support; rather, they are stepping stones for deepening cooperation in areas of mutually agreed interest.

There is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to these partnerships, and the SDPs can be expected to be functionally distinct based on the partners – this differentiated approach to partners was a key objective of the Strategic Compass. Although this individualised approach to partners also requires more political resources, it can become a critical part of adapting European security and defence policy to a changing European and global security environment. This diversification of partners is particularly important as the ramifications of competition between the United States (US) and China affect the EU and its partners alike and present them with similar challenges. This CSDS Policy Brief looks at the type of SDPs the EU has signed so far, and how political commitment is required to ensure the success of the partnerships. It is argued that unlocking the full potential of SDPs can help the EU and its like-minded partners weather the growing US-China rivalry.

The existing security and defence partnerships: a typology

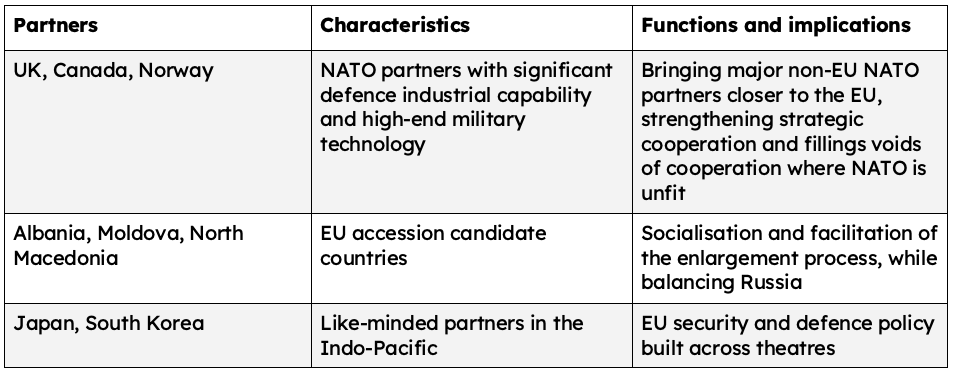

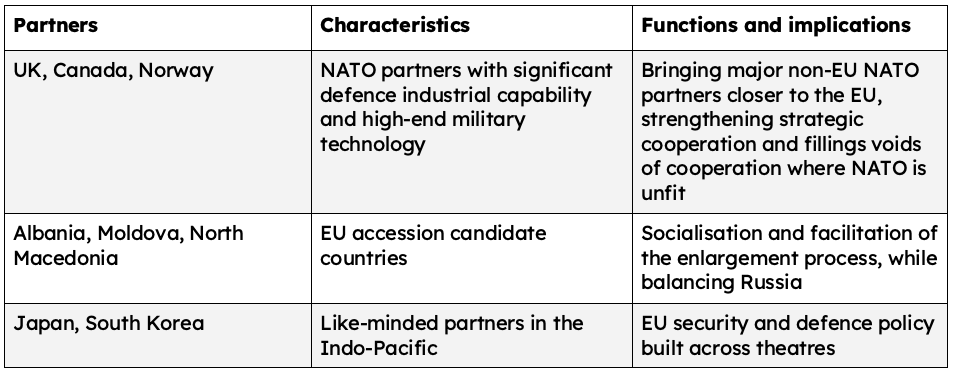

The Security and Defence Partnerships concluded in recent years all constitute bilateral partnerships between the EU and like-minded partners, but they vary significantly in scope, potential and political implications. The current partnerships can be largely divided into three categories. A first category includes the UK, Canada and Norway, and creates a framework for deepening cooperation with highly capable non-EU NATO member states. A second type of partnership includes the agreements with Albania, Moldova and North Macedonia, all located in the Western Balkans – a strategically and geographically highly important region for the EU – and all candidates for EU membership. A third category of partnership is global partnerships with Indo-Pacific nations, namely Japan and South Korea. These partners are highly capable and share concerns similar to the EU in the region. The partnerships differ in terms of function and political implications across these three categories.

The cooperation with partners from the first category is potentially the widest-ranging, not least because their ties in the realm of security and defence with European states already exist and are strong through NATO membership. At the same time, the SDPs with these partners allow the EU to deepen the relationship with them and therefore fill a void where NATO cannot provide the necessary frameworks for cooperation. First, the SDPs provide a more institutionalised framework for strategic dialogue and political coordination on structural challenges. Even if both Canada and the UK have a strong network of bilateral ties with different EU member states, adding this level of strategic dialogue directly with the EU changes the dynamic because it also allows for the identification of concrete ways of collaboration with EU tools and mechanisms. This is the second way in which the SDPs can provide a framework for cooperation: as the EU is becoming an increasingly important actor, especially in the defence industrial realm, the SDPs are an important step to bringing partner countries with advanced military and defence industrial capabilities closer to the Union. Furthermore, the conclusion of the SDPs in light of the uncertain trajectory of US involvement in European security and defence is also a strategy of mutual reassurance and building guardrails, as they have already allowed two key partners in European and transatlantic security to work closer to European counterparts through new channels of defence diplomacy. In this regard, the SDPs with Norway, the UK and Canada are crucial to European security cooperation.

The SDPs with Albania, Moldova and North Macedonia will be less relevant for the EU and its member states when it comes to defence industrial cooperation, but their conclusion is highly salient concerning potential EU enlargement and the geopolitics of the European project. All three states are EU candidates and hence on track to potentially join the Union one day, but Russia’s increasing influence in the region is a source of concern for the EU. Russia’s active disinformation campaigns and interference tend to embolden pro-Russian forces and weaken democratic governance and pro-EU movements. In terms of security, a Russian presence at the EU’s borders is anything but reassuring. The SDPs with these partners, hence, serve to balance Russia by boosting the enlargement process: it brings the three partners closer to the EU, supports them in tackling Russia’s influence in fields like hybrid threats and also already creates synergies in the areas related to the CSDP. This helps facilitate the adaptation of the countries to EU standards in the enlargement process. The conclusion of these partnerships is also a clear signal towards Russia that the European path chosen by the governments also emphasises their sovereign decision to choose their alliances and security partners. For the EU, these partnerships are also critical because the enhanced strategic dialogue with partners most exposed to Russian hybrid influence provides insights into best practices in tackling hybrid threats.

The EU’s partnerships with South Korea and Japan are again different in scope. As technologically advanced countries, Japan and South Korea bring a lot to the table when it comes to capability development and defence industrial cooperation. At the same time, the partnerships with these two countries are also linked to the geopolitical “big picture” and the EU’s global action. In recent years, the Indo-Pacific has become an increasingly important region for European security and defence: this is reflected in initiatives on the EU level, like the Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific or EU-Indo-Pacific interministerial fora, and at the level of member states, which elevated the relevance of the region in national strategies and also deployed assets to the region. The SDPs with Japan and South Korea are clearly aligned with these efforts. Beyond the potential material cooperation, they create a forum for strategic exchanges between the EU and its Indo-Pacific partners, which appears particularly relevant as increasing Sino-American competition affects Europeans and Asian states alike, albeit to varying degrees.

Table 1: The three categories of EU Security and Defence Partnerships

Source: author’s own

Partnerships need commitment

These functional distinctions constitute arguably the biggest asset of the SDPs. The approach of individual bilateral relationships based on the interests and priorities of other states certainly requires a higher level of political energy, as it implies a shift away from a “one-size-fits-all approach”. In other words, most external engagement and partnerships had the same institutional format – namely, one which best matched the EU’s internal functioning – instead of focusing on content and taking the partners’ priorities as a guiding line for designing the partnerships. Consequently, effectiveness, efficiency and the relevance of the EU’s foreign policy approaches remained relatively limited in many cases. It therefore represents a shift in strategic thinking in Brussels: compared to the past, the concept of the SDPs has allowed the EU to move on from this approach by designing these partnerships in a way that is more tailored to mutual interests.

In the future, defining these mutual interests and implementing corresponding solutions will most likely constitute the biggest challenge: the central weakness of the SDPs is that they do not include concrete action items or a roadmap for cooperation, but often a commitment to enhanced dialogue. Accordingly, the effectiveness of the SDPs depends significantly on political will at the highest level to pursue them and on bureaucratic bandwidth to follow through with the implementation. However, the SDPs facilitate this path by strengthening exchange on both the highest political level and the working level, making progress and cooperation easier to achieve on both levels. Although cooperation between the EU and partners can also be pursued through other ways of formalisation, as shown by the example of Norway’s association with the European Defence Agency (EDA), the SDPs might also become more relevant for partners in the future. The EU’s new SAFE legislation requires the signature of an SDP for third countries to benefit from the instrument, which indicates an increasing willingness to formalise relationships instead of granting access to EU instruments and funding to external partners “à la carte”.

In other words, the SDPs are not a silver bullet for enhancing cooperation with key partners, but they need commitment from both sides to seize the added value of the formalisation of the partnerships. A key asset is, however, that the formalisation of the relationship via an SDP already has a relatively high symbolic value and is already a strong political commitment, so that it is easier to follow through with the implementation of concrete projects. Given that all of the EU’s current partners are democracies and hence prone to government change due to electoral cycles, it is important for the EU to seize the momentum of political commitment of a partner. Even though the SDPs can also help build meaningful links on the working level, their actual effect is limited if the highest political level is openly reluctant to pursue or enhance cooperation with the EU. Nevertheless, the SDPs still build a good base for the partnership in the future because they are likely to facilitate re-engagement with a partner when forces more open to cooperation with the EU set the agenda again.

European security beyond institutional membership

Beyond the bilateral dimension and the individual relationship with the partners, the EU’s approach of concluding SDPs with key partners also makes a new contribution to the future of the European security order. This is especially the case as the trajectory of US engagement in European security and defence remains uncertain, and European states need to be prepared to take more responsibility for the continent’s security. While it is almost certain that the US will withdraw, at least partially, from its commitments in Europe, the central question for European states is the scope, speed and coordination with allies of this withdrawal. In either case, they need to be prepared for “burden-shifting” from the US to Europe. The SDPs can support this effort in several ways. They bring non-EU NATO member states closer to the EU and hence facilitate strategic dialogue and coordination. These enhanced dialogues and exchanges can promote trust among partners and the trust of partners in the EU, which might also make them more likely to pursue cooperation with the EU instead of insisting on solutions being pursued only through NATO. As there is a risk that the US might block certain decisions at the NATO level or just not consider certain tasks a NATO responsibility, the SDPs can help Europe bridge that gap. An example could be crisis management: it can be expected that the US will have little interest in supporting European states in crisis management in the South or South-East regions, unless the US sees a crisis in these areas directly linked to its own strategic interests. Albeit nominally a core task of NATO, pursuing crisis management via NATO at a time when the alliance needs its political attention for deterrence and collective defence might not be the best strategy. In contrast, the EU could step in here and bring its security and defence partners in as third countries.

The SDPs allow for European security cooperation to be extended beyond existing institutions into bilateral partnerships. As these partnerships add to an intense web of multinational defence cooperation formats in Europe – in 2023, it was estimated that around 200 of these formats existed – and a plethora of bilateral relationships, they therefore allow European states to create an increasingly dense web of formats for security cooperation. The key asset of the SDPs in this context is that they do not duplicate what already exists in Europe, but they do help close precisely existing gaps in security and defence cooperation or open new ways of doing so. The most recent example is the SDP between the EU and the UK. As most EU member states are also NATO members, cooperation and coordination with the UK on operational questions and defence strategy occur in the framework of NATO. However, not all challenges for the European security order can be sufficiently addressed through the alliance. This is especially the case in the defence industrial realm – critical for literally equipping Europe for the future challenges –, where NATO lacks mechanisms for financing and joint procurement. The SDP allows the EU and the UK to overcome this challenge and close an important gap in European defence cooperation, allowing them to jointly build a more robust European defence space.

Conclusion: mitigating the ramifications of US-China competition

The EU’s active approach towards concluding SDPs with partners outside Europe, namely in the Indo-Pacific, also reflects that European security goes beyond the European theatre. Besides the existing partnerships with Japan and South Korea, the EU is currently negotiating a similar agreement with Australia. Additionally, it may do so with India very soon, too. For European states, the connection of the European and the Indo-Pacific security theatres is a reality – with the most visible, but not the only, sign being the presence of North Korean soldiers in Ukraine. Given that European security hinges substantially on the US engagement in the continent, at least in the short-term, a scenario of particular concern for European states is a “two-theatre tragedy”: in this scenario, a conflict over Taiwan would require the US’ full political attention and military commitment, and the resulting withdrawal from European security would open a window of opportunity for further Russian aggression, either towards Ukraine, an EU member state or NATO ally. Even without the realisation of this worst-case scenario, the EU and its Indo-Pacific partners face a similar risk of abandonment by the US, which is likely to be used as a means of coercion by the Trump administration. Accordingly, closer strategic cooperation can allow both sides to enhance dialogue on the security dynamics across regions and jointly anticipate potential responses.

From a perspective of global order, the SDPs represent a coping mechanism of middle powers to mitigate the potential ramifications of US-China competition. Security dynamics in the Indo-Pacific also directly affect European interests, but just like East Asian partners, the EU has limited leverage. It seems hard to imagine a scenario where the EU or its East Asian partners manage to substantially alter the strategy of the US or China towards the respective other power and towards the Indo-Pacific. Yet, regional powers and the EU are, albeit to different degrees, directly affected by the trajectory and ramifications of US-China competition, given that a military escalation in the region could be expected to represent a considerable shock for global trade. Instead of choosing sides, the SDPs can be seen as a first step towards solidifying ties between states that do not want to fully align with the US or China. These stronger ties and coordination of strategies and interests can allow them to gain leverage vis-à-vis the great powers through cooperation and, therefore, mitigate the risks from great power competition.

__________

The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for Security, Diplomacy and Strategy (CSDS) or the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB).

ISSN (online): 2983-466X